Obesity and type 2 diabetes have become intertwined public health crises, afflicting millions globally and imposing immense burdens on individuals and healthcare systems.

Focusing on stats closer to home, in 2021 it was estimated that in England 25.9% of the adult population were obese, with a further 37.9% being overweight but not obese (1).

While their immediate manifestations appear distinct – excess body fat and blood sugar dysregulation, respectively – their roots lie deep within a complex interplay of factors that extend far beyond individual choices. Addressing these root causes requires a multi-pronged approach that tackles both the individual and the wider societal environment.

Body Mass Index - Not a Perfect Measure of Obesity

Obesity, characterised in the UK typically by a body mass index (BMI) exceeding 30, is a major risk factor for type 2 diabetes. BMI isn't a perfect measure of obesity, however. It has limitations that can potentially misclassify individuals:

Limitations of BMI:

- Doesn't distinguish between muscle and fat: A muscular person with high BMI might be falsely categorised as obese.

- Doesn't consider body composition: Fat distribution also plays a role. Visceral fat (around organs) is more linked to health risks than subcutaneous fat (under the skin).

- Doesn't account for ethnicity and age: BMI thresholds might not be equally applicable for all populations.

Beyond BMI, here are some ways to assess obesity more accurately:

- Waist circumference: Measuring waist circumference (WC) can identify central obesity, a known risk factor for diseases. Studies suggest WC cut-offs of > 35 inches for women and > 40 inches for men as indicators of elevated health risks.

- Body fat percentage: Measuring body fat percentage through methods like bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) or dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) provides a more precise picture of fat mass.

- Body composition analysis: Advanced techniques like bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS) or air displacement plethysmography (ADP) analyse lean muscle mass, fat mass, and water content for a comprehensive assessment.

- Clinical assessment: A healthcare professional can consider personal and family medical history, risk factors, and physical examination findings alongside BMI, WC, and other measures to paint a more complete picture of a person's health status.

Obesity and Chronic Inflammation: Intimately Connected

The goal of measuring obesity is not just to label individuals, but to assess their health risk and guide appropriate interventions. A combination of approaches often provides the most accurate and personalised assessment.

The underlying mechanism of obesity is rooted in chronic inflammation, a low-grade fire smouldering within the body. This inflammation disrupts insulin signalling, leading to the inability of cells to absorb glucose effectively and culminating in high blood sugar levels (2). This inflammatory state is fueled by multiple factors, including:

- Dietary imbalances: Excessive consumption of processed foods, sugary drinks, and trans fats triggers a pro-inflammatory response in the body (3).

- Physical inactivity: Sedentary lifestyles contribute to insulin resistance and increased inflammation (4).

- Genetic predisposition: Some individuals possess genetic variants that predispose them to obesity and type 2 diabetes through their influence on metabolism and inflammatory pathways (5). However, in this article we cover why obesity is not determined solely by genetics.

- Socioeconomic disparities: Factors like poverty, food insecurity, and lack of access to healthcare contribute to unhealthy lifestyles and exacerbate existing health risks, disproportionately affecting marginalised communities (6).

Beyond Individual Choices

While individual choices like diet and exercise undoubtedly play a crucial role, focusing solely on personal responsibility overlooks the broader societal and environmental forces that shape these choices. Consider the following:

- Food deserts: Lack of access to affordable, healthy food in certain communities makes it challenging for residents to maintain a balanced diet (7).

- Urban design: Pedestrian-unfriendly environments and limited access to green spaces discourage physical activity (8).

- Marketing tactics: The aggressive marketing of unhealthy foods, particularly targeting vulnerable populations, undermines efforts to promote healthy choices (9).

- Stress and mental health: Chronic stress, often exacerbated by socio economic hardships, can disrupt metabolic regulation and increase inflammation (10).

Breaking the Cycle: A Multi-pronged Approach

Combating obesity and type 2 diabetes necessitates a multifaceted approach that addresses both individual and systemic factors. Here are some key strategies:

- Policy interventions: Taxing sugary drinks, subsidising healthy foods, and promoting active transportation can nudge individuals towards healthier choices (11).

- Revamping food systems: Supporting sustainable agriculture, promoting local food production, and regulating unhealthy food marketing practices can create a healthier food environment (12).

-

Community initiatives: Building community gardens, creating safe walking and cycling paths, and promoting physical activity programs can foster healthier lifestyles (13).

- Addressing social determinants of health: Investing in education, job creation, and affordable housing can empower individuals to make healthy choices and reduce health inequities (14).

- Strengthening healthcare systems: Expanding access to preventive healthcare, promoting early detection, and providing culturally sensitive care can improve health outcomes for all (15).

The Role of Nutrition: A Focus on Inflammation

Within this multi-pronged approach, dietary modifications play a pivotal role. Reducing intake of processed foods, sugary drinks, and trans fats while increasing consumption of whole foods such as free range meats, fruits, vegetables, and whole grains can significantly decrease inflammation, while naturally limiting unhealthy fats and sugars.

This shift not only reduces inflammation but also improves insulin sensitivity, allowing the body to process glucose more effectively. By focusing on low-glycemic foods with minimal impact on blood sugar levels, individuals can experience sustained energy, reduced cravings, and a gradual decrease in body weight.

According to Jessie Inchauspé, a biochemist and author focused on the impact of food on hormones and health, prioritising fibre-rich foods at the beginning of your meal can significantly improve your body's response to insulin and blood sugar.

Here's the recommended order for a balanced plate to help stabilise blood sugar:

-

Start with the greens: Think of this as priming your digestive system. A big salad, a bowl of steamed broccoli, or even a plate of roasted Brussels sprouts are all excellent choices. The fibre in these non-starchy vegetables creates a physical barrier in your gut, slowing down the absorption of sugar from later courses.

- Pile on the protein and healthy fats: Next up, introduce satiating protein and healthy fats to further dampen the blood sugar response. Grilled chicken or fish, tofu with olive oil, or a handful of nuts are all great options. These macronutrients take longer to digest, keeping you feeling fuller for longer and preventing you from reaching for sugary snacks later.

- Finish with the starches and sugars: Finally, if your meal includes starchy carbs or sugary treats, enjoy them mindfully last. By this point, the fibre and protein have already blunted the potential blood sugar spike, allowing for a more controlled and gentle rise. Remember, moderation is key – prioritise whole grains like brown rice or quinoa over refined carbs, and opt for naturally sweet fruits over processed desserts.

Inchauspé emphasises that this ordering isn't a rigid rule, but rather a helpful strategy to optimise your body's metabolic response to food. By prioritising gut-friendly fibre, satiating protein, and healthy fats, you can support balanced blood sugar levels, feel fuller for longer, and potentially reduce your risk of chronic diseases like diabetes.

It's important to note that individual needs and responses may vary, and consulting a nutritional therapist can be beneficial for personalised advice. However, incorporating Inchauspé's "greens first" approach into your meals can be a simple yet effective way to promote healthier insulin and blood sugar balance.

Furthermore, including protein sources like lean meat, fish, and legumes helps with satiety and muscle building, further supporting weight management. Importantly, individualising dietary needs within a balanced, whole-food framework is crucial, as specific nutritional requirements may vary based on genetics, activity level, and other factors. Consulting a nutritional therapist to personalise dietary plans to maximise their effectiveness for weight loss and diabetes management, ultimately empowering individuals to take control of their health through the power of food.

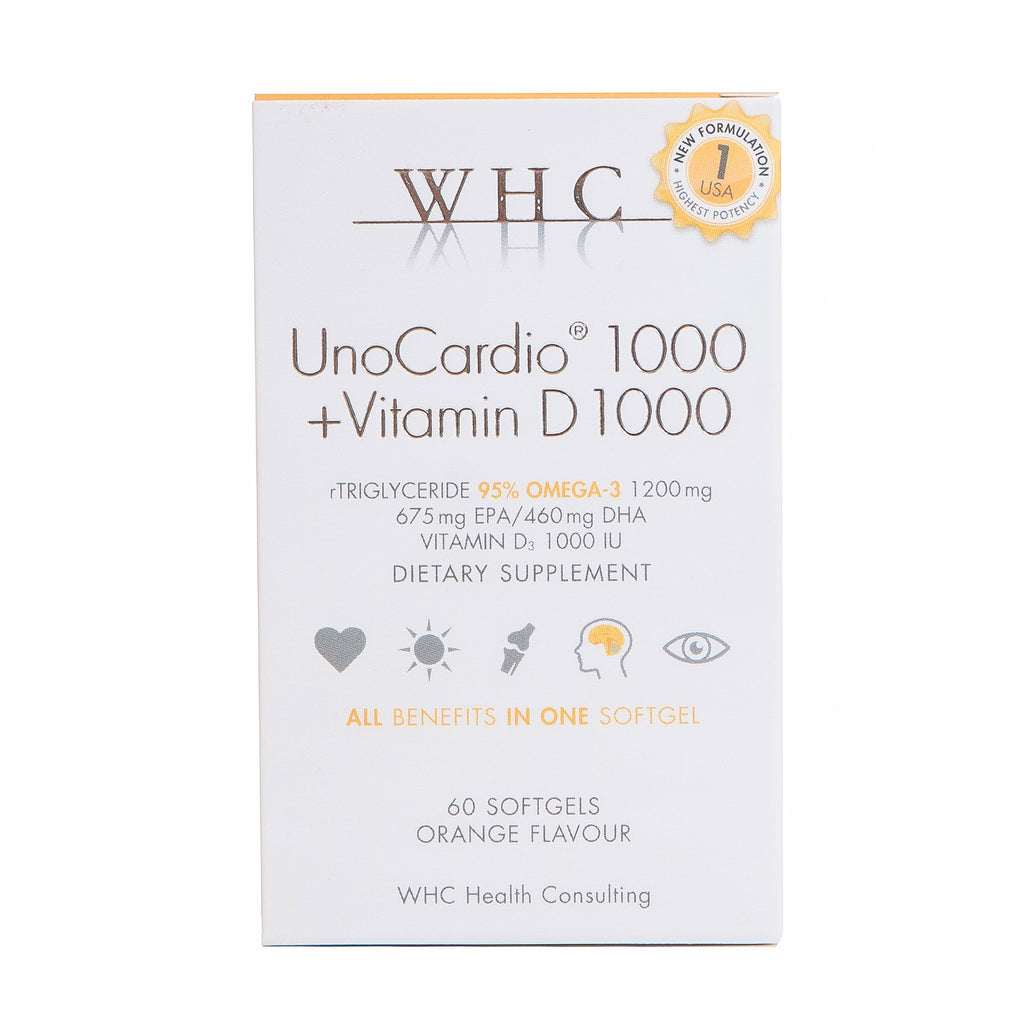

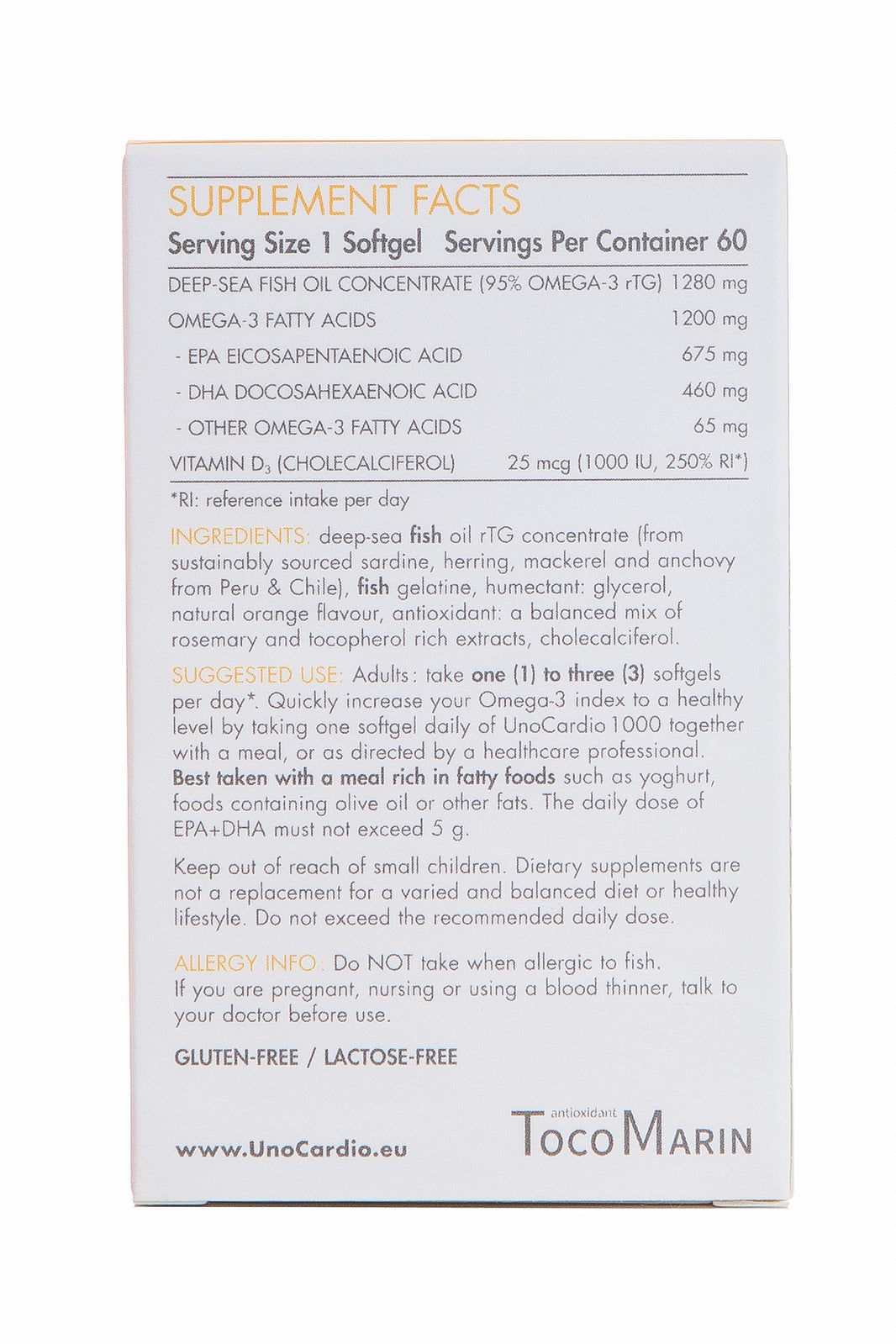

Additionally, incorporating specific nutrients, sometimes in the form of supplementation if a person's diet is not providing enough, like omega-3 fatty acids found in fish oil has emerged as a promising strategy.

Fish Oil and the Inflammation Puzzle

Fish oil, rich in omega-3 fatty acids, particularly eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), possesses potent anti-inflammatory properties. Research suggests that omega-3s can reduce inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), both elevated in individuals with obesity and type 2 diabetes (16, 17).

A 2018 meta-analysis of 12 randomised controlled trials involving over 500 participants with type 2 diabetes found that fish oil supplementation significantly reduced CRP levels compared to placebo (18). Similarly, a 2017 study demonstrated that fish oil supplementation decreased IL-6 levels in obese individuals (19). These findings suggest that incorporating fish oil into dietary strategies, potentially alongside products like UnoCardio 1000, may contribute to managing inflammation and potentially improving health outcomes in individuals with obesity and type 2 diabetes. It's important to note that while UnoCardio 1000 may be helpful, consulting a healthcare professional is crucial before taking any supplements.

Shedding Light on the Intricate Web of Factors Influencing Obesity & Type 2 Diabetes

Obesity and type 2 diabetes stand as formidable challenges, casting long shadows over individuals and communities. Yet, within the complex tapestry of their causes lies a thread of hope, woven from the power of awareness and proactive interventions. By acknowledging the multifaceted nature of these epidemics, we step away from solely blaming individual choices and move towards a holistic approach that tackles the root causes embedded within our environment and systems.

Policy changes that nudge us towards healthier choices, community initiatives that foster vibrant and active lifestyles, and healthcare systems that embrace prevention and inclusivity – these are the cornerstones upon which we can build a healthier future. Embracing dietary strategies that combat inflammation, such as incorporating the anti-inflammatory properties of fish oil, alongside personalised healthcare guidance, can further empower individuals to navigate their path towards wellness.

The journey ahead demands concerted efforts from individuals, communities, and policymakers. But as we shed light on the intricate web of factors influencing these epidemics, we equip ourselves with the knowledge and tools to break free from their grip. Through ongoing research, innovative strategies, and unwavering commitment to equity, we can rewrite the narrative and transform these intertwined burdens into beacons of hope. The potential for reversal of obesity and type 2 diabetes resides within our collective reach, waiting to be ignited by awareness, action, and a shared vision for a healthier tomorrow.

Written by Amy Morris, BSc (Hons) Nutritional Therapy. Amy has been a nutritional therapist for 12 years, specialising in recent years as a functional medicine nutritional therapist. Women’s health, and pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes prevention are Amy’s specialist areas. Diagnosed with a chronic condition called endometriosis at age 20, this is what motivated Amy to study nutrition. Amy has been in remission for 6 years now, attributing powerful nutrition, lifestyle and bio-identical hormone strategies she now shares with her clients.

Water for Health Ltd began trading in 2007 with the goal of positively affecting the lives of many. We still retain that mission because we believe that proper hydration and nutrition can make a massive difference to people’s health and quality of life. Click here to find out more.

Reference List:

- Baker, C. (2023, January 12). Obesity statistics. House of Commons Library. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN03336/SN03336.pdf

- Grundy, S. M. (2015). Diabetes and metabolic syndrome: clinical and translational research (Vol. 158). Academic Press.

- Patterson, R. E., & Remington, D. L. (2010). Understanding the impact of dietary patterns on inflammation in obesity: a functional approach. Current Obesity Reports, 1(4), 296-303.

- Pedersen, B. K., & Febbraio, M. A. (2008). Muscles, exercise and metabolic regulation: role of IL-6. Progress in Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 31(4), 294-301.

- Franks, P. W., & Hanson, R. L. (2017). Genetic determinants of human obesity and insulin resistance. Clinical Science, 131(13), 1455-1474.

- Williams, D. R. (2016). Race, socioeconomic status, and health: the added burden of poverty. Public Health Reports, 131(6), 10-16.

- Walker, R., Keane, C., & Kinsella, A. (2010). Food deserts: issues and solutions. Progress in Human Geography, 34(1), 68-82.

- Barton, J., & Pretty, J. (2010). Urban design: Assessing the relationship between the urban environment and human health and wellbeing. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 37(2), 293-312.

- Monteiro, C. A., Levy, R. B., & Claro, R. M. (2012). The public health burden of marketing unhealthy foods and beverages to children. The Journal of Pediatrics, 160(5), S10-S18.

- McEwen, B. S. (2003). Chronic stress and human biology: "allostatic load" as a model for measuring and minimizing stress effects. Science, 300(5624), 845-850.

- Brownell, K. D., Frieden, T. R., & Schlendorf, K. E. (2009). Food policy to combat obesity: what has the evidence been telling us? Health Affairs, 28(3), 892-907.

- Allen, G. H., & Demaine, H. (2014). Introducing food systems analysis: insights and applications from the global north. Routledge.

- Brownell, K. D., & Schlendorf, K. E. (2014). Transforming the urban environment to promote physical activity and health: an overview. Annual Review of Public Health, 35(1), 349-370.

- Marmot, M. (2005). Social determinants of health and the concept of the social gradient. Health Affairs, 24(2), 114-125.

- Aladjem, D., & Garfield, R. (2011). Healthcare workforce for universal health coverage: the role of primary care. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 89(10), 643-667.

- Calder, P. C. (2012). N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation, and immunity. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids, 87(3), 107-113.

- Siri-Tarino, P., Sun, Q., Zhang, W., Tang, W., Tong, W., Zhang, Y., ... & Yu, C. (2018). Fish oil supplementation and markers of inflammation in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients, 10(3), 305.

- Mori, T. A., Bao, D. Q., Burke, V., Puddifoot, J. N., Krause, L., Rennie, M. Y., & Wong, S. L. (2017). Effect of EPA and DHA on inflammatory markers in overweight and obese individuals: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 106(2), 280-289.

- Calder, P. C. (2013). Omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: towards an understanding of their anti-inflammatory properties. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 16(4), 245-250.

Leave a comment