It is no longer controversial to state that our gut bacteria – at least to a large extent – determine our health destiny.

When you do not have the correct balance in your body, it can set the stage for countless health problems, from short-term inconveniences like bloating, constipation or diarrhoea to more serious conditions such as Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, depression, anxiety, autoimmune disorders and obesity.

With a wealth of scientific data continuing to show that changes in our microbiome play a critical role in the regulation of various biological processes, there’s never been a better time to nurture diversity among the tens of trillions of bacteria living within us.

In fact, we should probably think of the microbiome as another organ entirely: one whose influence on our overall wellbeing is unparalleled.

In this article, we intend to look at the whole picture: what constitutes good gut health; which factors influence diversity among the trillions of microbes in your gut, known as the microbiota; which symptoms highlight an imbalance of such organisms; and which critical factors are consistently overlooked by the majority of voices on this topic.

The Gut is a Garden

It is easy to view the gut as a garden, and to correspondingly see oneself as a gardener whose role it is to provide the water, soil, sunlight and nutrients needed to make sure it blossoms.

While pharmaceuticals such as antibiotics and even non-antibiotic drugs negatively affect the soil, consumption of probiotic foods can lead to a diverse bacterial community (‘microbiome’) with an important array of functions: or, to extend the analogy further, to a well-nourished garden teeming with colourful flora.

Like an avid horticulturalist, it is our job to “weed out” the harmful elements in our garden, in this case excessive bad bacteria, and strive for an optimal balance. (More scientific study is needed, but the ratio most often quoted in the literature is 85% so-called ‘good’ bacteria to 15% bad.)

We must also ensure the conditions are right within the gut to stimulate the proliferation of friendly bacteria when we feed and fertilise the soil. After all, you wouldn’t expect plants to grow without light – would you?

Because so many elements of modern living hurt our microbiomes – elements we intend to summarise in this article – our gardens are increasingly besieged by weeds and bugs. The benefits of encouraging good microorganisms to flourish, and thereby crowd out those competitive bugs and restore harmony, are obvious.

Bacteria Help to Ensure Smooth Digestion & Reduce Bloating

Over 1,000 species of gut bacteria line the digestive system, pocketed throughout the stomach, small intestine and large intestine. They are not distributed evenly, however, with the latter containing around 10,000 times more bacteria per teaspoon than the small intestine.

One of the many important duties of this voluminous population is to help digest food. As outlined in a 2018 paper in the BMJ, this includes providing “essential capacities for the fermentation of non-digestible substrates like dietary fibres and endogenous intestinal mucus. This fermentation supports the growth of specialist microbes that produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and gases.”

In many cases, if we don’t have enough good bacteria chomping their way through those indigestible fibres, the consequence is bloating, gas and post-prandial discomfort. The way bacterial enzymes feast upon complex and branched sugars found in vegetables and fruit is but one of many fascinating processes of the digestive system.

Time and time again, digestive complaints such as Irritable Bowel Disease (IBD) have been linked with gut barrier dysfunction and alterations in the microbiome. The same applies to Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis and other chronic digestive orders. Is it any wonder given the important functions these bacteria perform?

Nurture the Mind-Gut Connection to Improve Mood & Sleep

Because of how predictive it is of other processes in the body, the gut is often described as a Second Brain. It’s not hard to see why: the Enteric Nervous System exists in every part of your gut, and neurotransmitters – identical to those in the brain – are continually relaying chemical signals from one quadrant of the gut to another. This includes intelligence on hostile intruders like bacteria, viruses or toxins from contaminated food.

We have come to realise that ‘gut feeling’ is more than just a well-worn expression: it describes a complex mind-gut connection which is rooted in reality and keenly perceived by each of us.

The communicative flow of neurons, chemicals and hormones linking the brain and gut relays information about our mood, hunger, stress levels and more.

In fact, just about everything you think or feel manifests itself in the pit of your stomach, and this sensory network is distributed over the entire surface area of the gut – a space 200 times larger than the surface area of our skin.

| “Twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, our GI tract, enteric nervous system, and brain are in constant communication. And this communication network may be more important for your overall health and well-being than you ever could have imagined.” – Emeran Mayer, The Mind-Gut Connection |

Did you know that the gut microbiota actually regulates serotonin, the neurotransmitter that helps with sleeping, eating, digestion and feelings of happiness?

Much of what we have learned about the mind-gut axis comes from studies on microbe-free mice, which show not only that germ-free mice exhibit reckless behaviour but also poor memories. Further studies show that when certain microbes are implanted, the characteristics of the mice change; in one way or another, the microbiota affects levels of chemical messengers in the brain, which in turn alters the behaviour of the host organism.

The term “psychobiotics” was coined by Dinan et al (2013) to suggest the potential of live bacteria in mental disorder therapy, and indeed scientific studies have identified psychobiotics which provide appreciable antidepressant, anti-anxiety and anti-autism effects.

More placebo-controlled trials are needed in this area, particular to pinpoint optimum strains, dosage and treatment period, but preliminary evidence is promising.

How Does the Microbiome ‘Prime’ Your Immune System?

Did you know that the gut is home to 70 percent of the body’s immune cells? In this context, immune response is completely tied to goings-on in the gastrointestinal tract.

As well as enabling immune tolerance of dietary and environmental antigens, the bacterial population ‘primes’ the immune system to protect against invading pathogens (bacteria, fungi, protozoa, viruses etc) which can enter the body via food, drink, eyes, ears, mouth, nose and open wounds.

Diverse gut flora early in life also teaches cells of the immune system to differentiate between good and bad bacteria. After all, in order to turn its powers on the correct targets, it must be capable of identifying friend from foe.

This is a big part of the reason why children delivered via Caesarian section – i.e. those who miss out on microbes in the birth canal – are at greater risk of obesity, asthma and diabetes.

Faecal transplantation in colitis patients, and probiotic supplementation more generally, has shown huge benefit in a number of clinical trials. The correlation between certain gut bacteria and immune response was highlighted in one University of Chicago study in 2018, which demonstrated that specific bacteria in the intestine could improve the response rate to immunotherapy for patients being treated for advanced melanoma.

The bacteria in question appeared to “enhance T-cell infiltration into the tumour microenvironment and augment T-cell killing of cancer cells, increasing the odds of a vigorous and durable response.”

Thomas Gajewski, MD, Professor of Cancer Immunotherapy at the University, was quoted as saying: “The gut microbiota has a more profound effect than we previously imagined.”

The fact that cancer patients who benefited from a higher ratio of ‘good’ bacteria to ‘bad’ bacteria consistently showed a clinical response (i.e. a reduction in tumour size) certainly underscores the value of maintaining a healthy balance.

I Heart Gut Bacteria: The Effect on Heart Health

Although it is too early to draw firm conclusions about the specific link between bacterial composition and heart health, several human and animal studies have suggested that an altered microbiota influences the pathogenetic mechanisms driving cardiovascular disease.

Or to put it another way, animals with hypertension exhibit reduced bacterial diversity, with decreased quantities of acetate and butyrate. The latter are short-chain fatty acids which exert numerous beneficial effects on energy metabolism, increasing fatty acid oxidation in multiple tissues and reducing fat storage in white adipose tissue.

| “There’s a complex interplay between the microbes in our intestines and most of the systems in our bodies, including the vascular, nervous, endocrine and immune systems. All of these relationships are highly relevant to cardiovascular health.” – Dr. JoAnn Manson, Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School |

Our microbial make-up can also affect the levels of LDL cholesterol in our blood and even our blood pressure – which is perhaps why high-strength probiotic consumption has been shown to lower blood pressure.

Bacteria’s contributory role in the development of other cardiometabolic disorders such as obesity and type 2 diabetes continues to be investigated, and though we can speculate that imbalanced gut bacteria counts as a risk factor for heart disease, pinning down a ‘treatment’ is trickier.

That said, few would argue that building a healthier microbiome will have anything but a positive effect on your cardiovascular system.

Focus On Your Gut for Clear, Radiant Skin

It mightn’t receive as much attention as the gut-brain axis, but the interplay between gut and skin is a fascinating and growing area of research. Not that it’s in any way new: a link was first suggested almost 90 years ago.

Just like the intestinal tract, the planes, folds and crannies of the skin are home to microbes. So, too, are sweat glands, hair follicles and nasal passages (yes, you’re discharging microbes when you sneeze!). When you think about it, the gut and skin are similar in function since both act as as ‘interfaces’ with the external environment.

What does all this mean? In essence, it means that by focusing on your gut, eliminating pro-inflammatory foods and addressing underlying gut pathologies, you might be able to reverse inflammatory skin conditions such as eczema, acne and psoriasis. Certain strains of bacteria have also been shown to improve skin hydration and elasticity.

Clinical studies highlight a significant correlation between gut pathologies and skin conditions, for example between celiac disease and psoriasis or rosacea and SIBO. Gut barrier dysfunction can also burden the skin with endotoxins, and the microbiome has even been shown to support the restoration of skin homeostasis after ultraviolet (UV) radiation exposure.

Diet, as we know, can influence the appearance of skin; while metabolites of green tea catechins and polyphenols from fruit can be incorporated into the skin and reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines, gluten and dairy can trigger flare-ups like eczema and acne.

Incidentally, many have enjoyed success in clearing up skin trouble by switching to a Paleo diet, which is built largely around meat, vegetables and bone broth, although also allowing for some nuts, seeds and fruit.

Future research will be dedicated to enhancing our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the gut-skin axis, and assessing the therapeutic potential of fine-tuning the gut environment via lifestyle and diet.

How Friendly Flora Can Help You Stay Lean

According to a new study by researchers at Sweden’s Lund University, certain metabolites in our blood are connected to both obesity and the composition of our gut microbiome.

After analysing blood plasma and stool samples from 674 respondents, the researchers noted 19 separate metabolites which could reliably be tied to the person’s BMI, including glutamate and and BCAA (branched-chain and aromatic amino acids). These obesity-linked metabolites were also linked to four types of intestinal bacteria.

In simple terms, our intestinal flora seems to correlate with our obesity risk. And this is far from novel: when scientists transferred bacteria from naturally obese mice to germ-free mice, the latter gained weight; but when gut bacteria was transferred from naturally lean mice, they stayed lean.

| “In the future, the nutritional value and effects of food will involve significant consideration of our microbiota, and developing healthy, nutritious foods will be done from the inside out, not just the outside in.” – Jeffrey Gordon |

Furthermore, studies show that the microbial population of obese people is far less diverse than their lean counterparts. This might explain why some dieters watch the pounds melt off while others struggle.

According to Dr. Purna Kashyap, a gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, “gut bacteria are likely an important determinant of the degree of weight loss attained following lifestyle and dietary intervention.”

Dr. Kashyap was commenting on the results of a 2018 study which found that an increased ability to use certain carbohydrates correlated with a failure to lose as much weight.

The doctor even suggested that in future, weight-loss plans should be based on an individual’s gut bacteria; and that modifying the makeup of bacteria using probiotics should be the first priority, before commencing a diet or exercise program.

Strong Gut, Healthy Bones: Assessing the Gut-Bone Axis

A new frontier of research is focusing on the links between intestinal flora and skeletal health.

According to a 2017 review paper, “findings from preclinical studies support that gut microbes positively impact bone mineral density and strength parameters. Moreover, administration of beneficial bacteria (probiotics) in preclinical models has demonstrated higher bone mineralization and greater bone strength.”

The genus which has repeatedly exhibited beneficial effects for bone health is Lactobacillus, and because the health of the skeletal system is largely determined by early life development, its effectiveness is dependent on early administration.

It is not a question, of course, of plying youngsters with probiotic supplements but rather ensuring a healthy and diverse microbiome from the get-go. Children born via natural birth benefit most from Lactibacilli, as explained in Martin J Blaser’s book Missing Microbes:

“Whether the birth is fast or slow, the formerly germ-free baby soon comes into contact with the lactobacilli. The baby’s skin is a sponge, taking up the vaginal microbes rubbing against it… The first fluids a baby sucks in contain its mother’s microbes…

“Once born, the baby instinctively reaches his mouth, now full of lactobacilli, toward his mother’s nipple and begins to suck. The birth process introduces lactobacilli to the first milk that goes into the baby. This interaction could not be more perfect.

“The lactobacilli become the earliest organisms to dominate the infant’s formerly sterile gastrointestinal tract; they are the foundation of the microbial populations that succeed them. The baby now has everything it needs to begin independent life.”

A number of exciting human studies are on the horizon, with the aim of identifying how the gut microbiota may be influenced to preserve bone health and cut the risk of osteoporosis. In the UK, the cost of treating all osteoporotic fractures in just postmenopausal women is predicted to hit more than £2 billion by 2020.

As demonstrated, the effects of gut bacteria on our hearts, brains, digestive and immune systems, skeletons and skin are truly profound. The influence on our collective obesity risk is also considerable.

We are probably just scratching the surface as to the foundational importance of gut health on our overall wellbeing.

Dysbiosis: What Is It, What Are the Symptoms?

When the amount of friendly bacteria living in our gut is insufficient, it disrupts intestinal homeostasis and leaves room for harmful bacteria and micro-organisms to flourish.

This imbalance – commonly known as dysbiosis – is linked with the pathogenesis of both intestinal and extra-intestinal disorders, including but not limited to inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), asthma, metabolic syndrome, leaky gut, diverticulitis, colon cancer, Crohn’s disease and cardiovascular disease.

Alterations in our gut bacteria which decrease biodiversity and species richness can stem from exposure to multiple environmental factors such as: diet, toxins (i.e. pesticides on unwashed fruit), alcohol and pharmaceutical drugs and pathogens.

Poor dental hygiene and elevated stress levels are two more triggers. In the next section, we’ll touch upon a range of factors which impact the gut microbiota.

Symptoms of microbial dysbiosis are virtually countless and include:

• Stomach upset (gas, bloating, cramping, constipation, diarrhoea etc)

• Brain fog

• Heightened food sensitivity

• Fatigue

• Halitosis (chronic bad breath)

• Sinus congestion

• Anxiety

• Chest pain

• Depression

Because symptoms of dysbiosis are often vague, it is not uncommon for them to go unnoticed and undiagnosed. Even worse, they can be misdiagnosed by health care clinicians who overlook the gut entirely.

Practitioners in the know, however, will consider the possibility of dysbiosis and commission comprehensive digestive stool analysis or an organic acid test to determine whether gut bacteria is imbalanced.

They may then assess your diet and lifestyle and tailor a nutrition plan to correct the dysbiosis by repopulating your colony of friendly bacteria.

Which Factors Affect the Wellbeing of Your Gut?

The composition of intestinal microbiota is influenced by a whole raft of factors over the course of one’s lifetime, and the microbial make-up of your gut is every bit as unique as a fingerprint.

In this section, we’ll give a summary of the various factors which affect on your gut diversity, and we’ll do so with reference to the most credible scientific literature.

• Age

There are substantial age-related changes in the composition of gut bacteria. Indeed, our microbiome undergoes its most pronounced transformations during infancy and old age, and our immune systems are also at their least stable during these two critical junctures of life.

What is not yet well understood is whether changes to the complex community of microorganisms within us are the cause or consequence of the ageing process.

After all, alterations in the microbiomes of elderly people may be linked with lifestyle factors (sedentariness contributes to slower gut motility, for example), diet, increased intake of medications including anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics etc.

Whatever the cause, it is increasingly believed that disruptions in the microbiome contribute to age-related health conditions such as bowel disorders, Alzheimer’s and hypertension.

Observations indicate that the intestinal bacteria commonly found to be reduced in the elderly is the type which helps to maintain immune tolerance in the gut, specifically bifidobacteria, lactobacilli and bacteriodes.

Conversely, opportunistic bacteria which provoke intestinal inflammation are often elevated.

As well as reduced diversity, elderly people suffer from diminished microbiota-related metabolic capacity such as lower short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) levels of butyrate, propionate and acetate.

These essential SCFAs have numerous functions including the regulation of mucus production, supporting gut barrier integrity and providing an energy source for colonic epithelium.

Incidentally, the consumption of dietary fibre is correlated with greater SCFA production and less gut inflammation in the elderly.

• Sex

Males and females are known to exhibit gender-specific differences in both their gut microbiota composition and also their immune system.

These can largely be attributed to different concentrations of sex steroids such as testosterone and progesterone, and explain why disease risks vary between men and women.

Tests on mice suggest that sex differences in the microbiome emerge during puberty and continue to diverge into adulthood.

One particular research paper published in the journal Frontiers in Immunology concluded by saying that “microbiota-independent gender immune differences contribute to the selection of a gender-specific gut microbiota composition, which in turn further drives gender immune differences. Therefore, gender should be considered in the development of strategies to target the gut microbiota in different disorders.”

In plain English, the gut is but another area where men and women differ.

Another recent trial on humans assessed the effect of anti-inflammatory medication on men and women. After a course of the drugs, females were shown to have a stronger intestinal barrier and greater diversity of gut microbes.

• Diet: Sugar, Gluten and Dairy Can Damage Your Gut

Eating for the gut entails its fair share of do’s and don’ts. While sugar and artificial sweeteners are toxic to beneficial bacteria and thus best avoided, fibre is vitally important in that it provides food for microbes. Fat – which has long been unfairly demonised – is essential for gut health as it is required for proper nutrient absorption and can relieve constipation.

Make sure your diet includes core microbiota-supporting nutrients such as B vitamins, folate, zinc, vitamins C and D, magnesium, calcium and manganese. Broadly speaking, these will help to regulate inflammation and markers of chronic disease.

Dark, leafy greens, fatty fish, nuts, seeds and lean, responsibly-sourced grass-fed meat should be staples.

| “When you look at populations that eat real food that’s high in fibre, and more plant-based foods, you’re going to see they have a more robust microbiota, with more genetic diversity, healthier species and fewer pathogenic bacteria living in the gut.” – Meghan Jardine |

It would be remiss not to mention gluten or dairy, both of which we touched upon in the Gut-Skin Axis section.

The damaging effects of gluten on the microbiome are well documented, and not just for those with celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity; for everyone.

Gluten obstructs the proper breakdown and absorption of nutrients, which can serve to effectively turn the dial on inflammation, damaging tissues and even leading to cases of leaky gut. This is a condition characterised by alterations in ‘bowel wall permeability’ which allow toxins, bacteria and undigested food particles to spill from the intestines and move through the body via the bloodstream.

Gluten also appears to have a pro-diabetogenic effect, as outlined in a 2013 Mayo Clinic mice study, specifically by altering the gut microbiome.

As for dairy, we know that some people are more sensitive than others. But we must all exercise caution. Studies on children show that dairy is negatively associated with species richness and diversity.

What’s more, modern farming means dairy products can contain traces of hormones and antibiotics, both of which have a significant adverse effect on your microbiome.

We should be careful with wheat, too, due to the presence of glyphosate residues. Glyphosate – the active ingredient in the herbicide Roundup – has been proven to disrupt gut bacteria in animals, killing beneficial forms and setting the stage for an overgrowth of pathogens. It is also a likely cause of leaky gut, since it compromises the tight junctions of the intestines.

Body weight is, of course, closely associated with diet – research suggests that BMI correlates with certain bacterial strains.

In a 2016 study of 39 men and 36 post-menopausal women, “after correcting for age and sex, 66 bacterial taxa at the genus level were found to be associated with BMI and plasma lipids.”

The results indicated not only that gut microbiota differed between sexes, but that differences were often influenced by the grade of obesity.

Maintaining a gut-friendly diet while keeping your BMI in check, therefore, appears to be the best course of action.

• Method of Birth & Breastfeeding

Cesarian delivery compromises the natural microbial handoff from mother to child, depriving the baby of beneficial lactobacilli and bacteroides.

For this reason the founding microbial populations present in infants delivered via C-section are not those determined by millennia of human evolution, and epidemiological evidence has frequently shown a link between this method of delivery and outcomes such as obesity, celiac disease and type 1 diabetes.

In England, 11.5% of expectant mothers have an elective caesarean (up from 4% in 1980) and 15.6% have an unplanned caesarean (up from 5%).

In the U.S., more than a third of deliveries are by C-section. A great many infants are thus deprived of microbes specific to their mother, a form of natural bacterial inoculation which helps educate the developing immune system and keep inflammation in check.

Studies show that babies born by Cesarian delivery exhibit particularly low bacterial richness and diversity.

Breastfeeding, too, has a huge influence on short- and long-term gut health; individuals who were breastfed as infants generally have a decreased risk of diabetes, obesity, gastroenteritis, pneumonia and diarrhoea-related diseases.

| “Mother’s milk shepherds her child’s microbiota assembly to ensure that the most beneficial community possible takes up residence.” – The Good Gut |

Breast milk provides complete nutrition for the baby, not only by delivering appreciable carbohydrates, fat and protein but countless health-promoting and bioactive compounds such as Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMOs) which nourish bacteria in the baby’s gut.

As is the case for children delivered via C-section, babies who are not breastfed exhibit a lower diversity of microbes. They also exhibit a smaller thymus – a lymphoid organ which produces T-lymphocytes for the immune system – than their breastfed counterparts.

For this reason and others, the World Health Organisation recommends providing breast milk for infants for up to two years and beyond.

Of course, irrespective of birth method and breastfeeding, your mother’s microbiome will influence your own. According to a 2018 study by the University of Virginia, the health of the mother’s gut is a key contributor to the child’s autism risk.

• Medication: How Pharmaceutical Drugs Hurt Your Microbiome

Broad-spectrum antibiotics are indiscriminate killers: while they wipe out harmful bacteria, they also decimate the good bugs.

In his book Missing Microbes, Martin Blaser, MD, describes the problem thus: “It is like carpet bombing when a laserlike strike is needed.”

And it’s not just your own antibiotic usage; if your mother used antibiotics, it will have influenced your resident microbes when you were born. The closer the antibiotic administration to birth, the greater the likelihood of reduced bacterial richness in the infant gut, decreased levels of Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria, and a heightened risk of childhood obesity.

Antibiotics are far from the only problem. According to 2018 research from the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Germany, almost one-quarter of 1,000 non-antibiotic drugs tested hampered the growth of at least one bacterial species, and in some cases a handful.

The researchers looked at an extensive range of drugs from cancer therapies to antipsychotics, and noted that many of them had antibiotic-like side effects such as gastrointestinal complaints.

Amazingly, 40 drugs designed to target human cells rather than bacteria hindered 10 or more species of gut bacteria!

• Underlying Medical Conditions

Most medical conditions are, by definition, treated with some form of medication; however, alterations in intestinal microbiota occur even when no medication is taken.

You see, our gut influences our health but the connection is bi-directional because our health also influences our gut. Chronic diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease and cancer, as well as obesity and autism, alter the composition of microbes just as microbes influence those conditions in numerous ways.

| “While life has always been a struggle for gut microbes, never has this been more the case than today, given what they are facing in the Western world.” – The Good Gut |

Take stress as just one example: psychological strain can actually increase the permeability of the gastrointestinal lining, leading to leaky gut.

Studies on students during exam time showed that high stress levels resulted in a depletion of friendly bacteria including Lactobacilli.

In addition to some of the factors we list in this article, the authors of a 2015 research paper entitled ‘Impacts of Gut Bacteria on Human Health and Disease’ contend that illness and host secretions (e.g., gastric acid, bile, digestive enzymes and mucus) play a role in determining the state of gut bacteria.

• Food Supplements: Which Products Support Diversity?

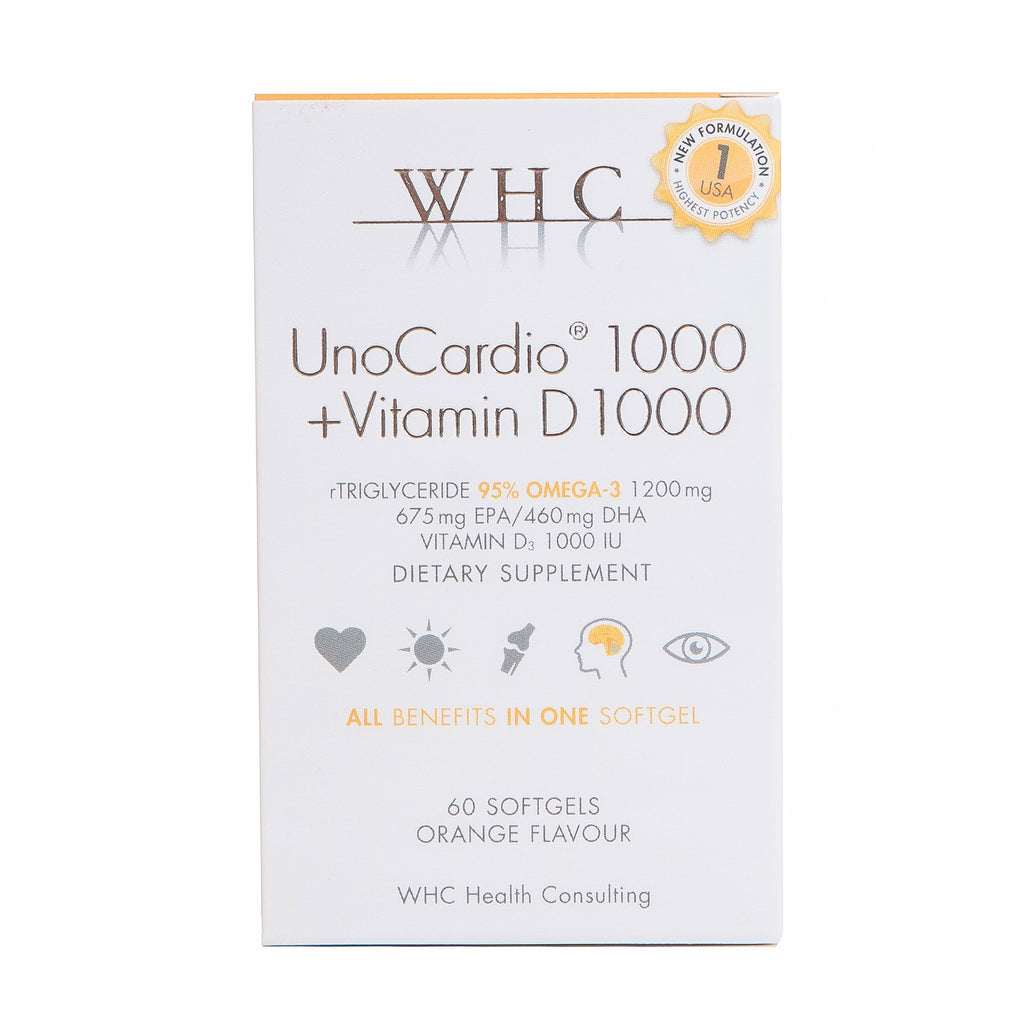

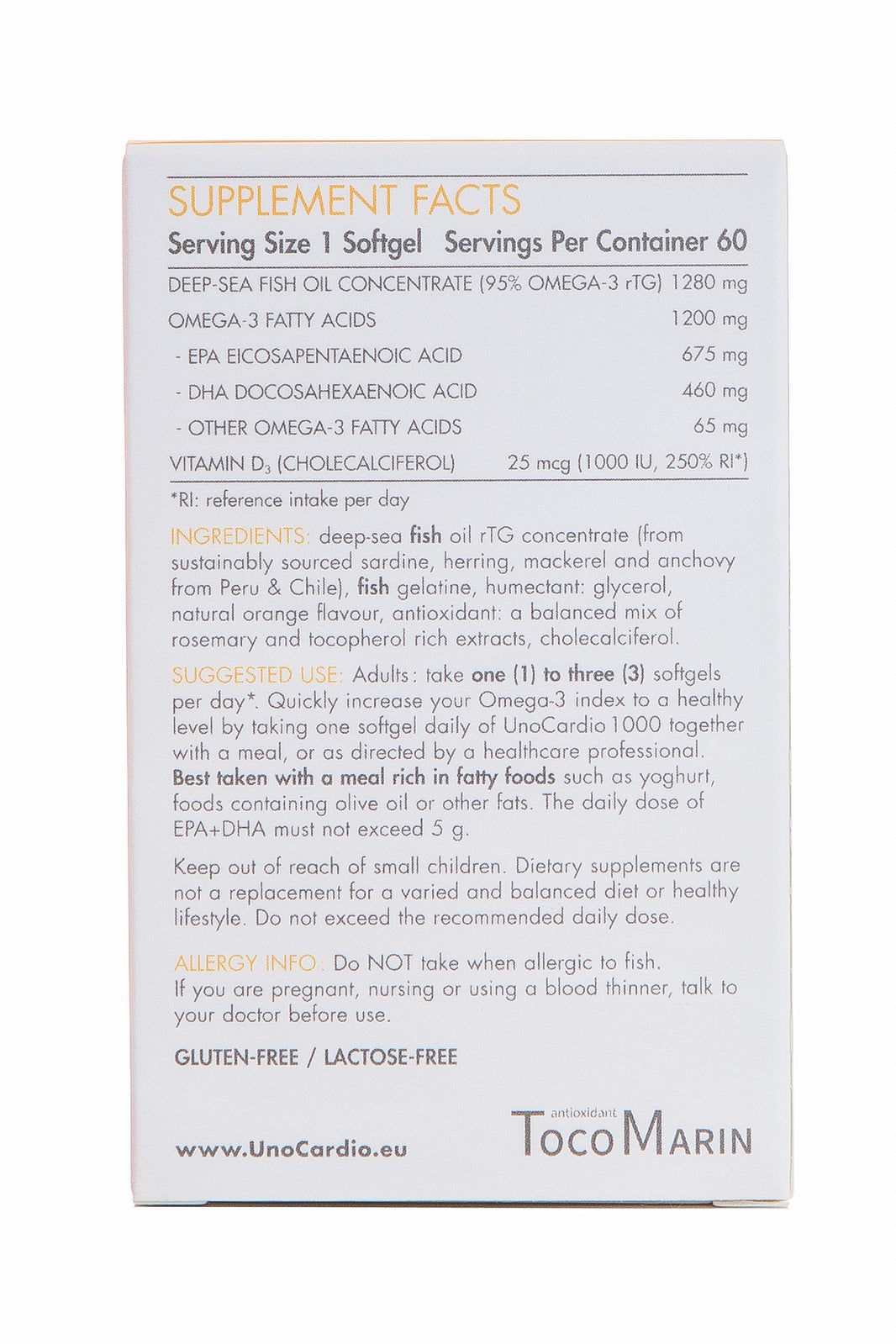

Don’t discount the effect of dietary supplements on gut health. Let’s take two of the most popular daily supplements: vitamin D and omega-3.

Vitamin D helps in several important ways. For one, it facilitates the production of antimicrobial peptides in the oral cavity which enables a healthier oral microbiome.

Vitamin D deficiency also decreases the production of defensins, anti-microbial molecules which are key to the maintenance of healthy gut flora.

In a 2016 study on mice, an insufficient supply of vitamin D was shown to aggravate gut flora imbalance, contributing to full-scale fatty liver and metabolic syndrome.

Another study from the same year, this time on humans, found that vitamin D deficiency alters the intestinal microbiome, reducing B vitamin production in the gut and adversely affecting the immune system.

At this stage, it is abundantly clear that achieving an adequate vitamin D status is beneficial for gut health. Given our climate, vitamin D supplements are a necessity rather than a luxury.

The effect of omega-3 on gut flora is similarly significant, as studies show that a higher intake of Essential Fatty Acids corresponds with greater microbial diversity, irrespective of fibre intake.

Omega-3s also appear to support Lachnospiraceae, a type of bacteria which helps protect against colon cancer.

• External Environment

Our obsessive pursuit of cleanliness is yet another facet of modern life which reduces microbial health. This is just one reason why the foraging Hazda tribe benefits from far superior gut diversity than typical Westerners.

From over-clean, sterilised homes to the widespread use of hand sanitisers, our commitment to achieving high standards of hygiene serves to disrupt our microbial make-up.

In contrast, bacteria-rich environments such as traditional farms can have protective health effects and lay the groundwork for species diversity (Mosca et al., 2016).

| “Bacteria come at us from all directions: other people, food, furniture, clothing, cars, buildings, trees, pets, even the air we breathe.” – Michael Specter |

Even the small matter of whether or not you own a pet can alter gut microbiota: in one 2017 study, early-life exposure to household pets enriched the abundance of Oscillospira and/or Ruminococcus, microbes associated with lower risks of allergic disease and obesity.

Additional external factors such as geography (urban vs rural) and pollution should not be overlooked. Just as microbiota are sensitive to diet, drugs and lifestyle, they are also sensitive to environmental pollutants such as heavy metals, pesticides, nanomaterials etc.

In several studies, increased air pollution exposure has been shown to correlate with reduced gut microbial taxa as well as increased blood cholesterol and the subsequent formation of arterial plaque.

• Exercise and Fitness: How Physical Activity Powers Up the Microbiome

Given the multitude of physiological benefits which stem from physical activity, it seems simplistic to even state them.

However, maintaining a good level of cardiorespiratory fitness is absolutely key to nurturing a healthy microbiome.

Physical activity corresponds favourably with health-promoting bacteria, particularly Akkermansia and Bifidobacterium, with one 2014 study identifying 22 distinct bacteria associated with professional sportsmen.

Higher fitness levels are also linked with improved butyrate production. Butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid which provides energy to colon cells and acts as a cellular mediator to regulate gut cell function.

The microbial benefits of exercise are believed to be transient, meaning exercise needs to be done consistently or the microbiome will revert to type.

• Circadian Rhythm

Circadian rhythm is a term used to describe various biochemical processes which follow a 24-hour cycle, what we commonly refer to as our body clock.

It is important to consider body clock in relation to gut health, and this is yet another bi-directional association: factors that affect the integrity of the microbiome influence our circadian rhythms and vice versa.

Disturbances in our circadian rhythm provoked by irregular sleep patterns or increased energy expenditure at unusual times of day increase the vulnerability of intestinal cells to injury.

Believe it or not, our intestinal bacteria actually have their own circadian rhythms, phases of rest and activity which affect the balance and types of microbes occupying in the GI tract.

The most recent research suggests that microbes depend on three primary factors to determine their rhythms: your diet, the time you eat and your sleep-wake cycle.

Eating late at night can disrupt the intestinal colony’s circadian rhythm and set the stage for obesity – a topic we covered earlier.

Maintaining a consistent sleep schedule, and eating the right foods at sensible intervals, is the way forward.

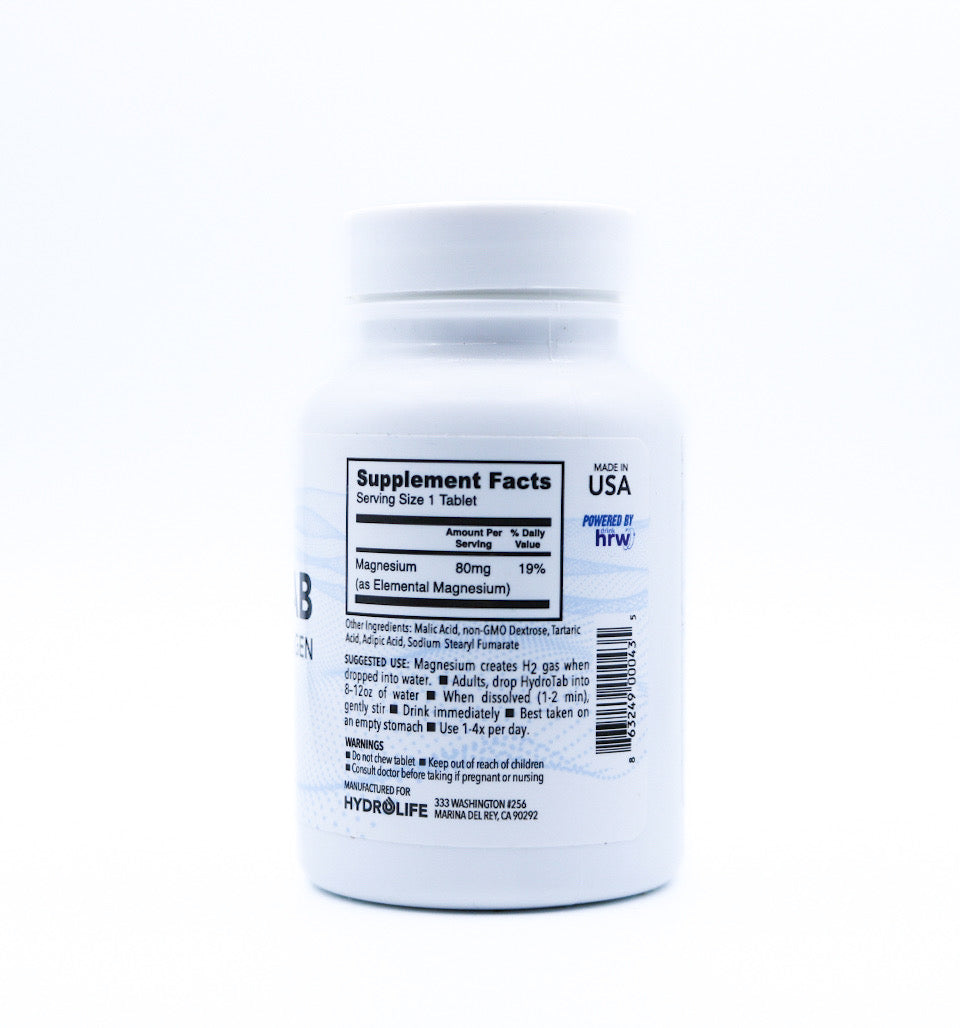

• pH and Electrolyte Balance

Bacterial balance is intimately connected to your body’s pH. If you fail to maintain a healthy pH in the gastrointestinal tract, and make the mistake of eating an overly acidic diet, you will be unable to sustain the necessary equilibrium of enzymes and microbes needed to keep your digestive system working.

The fact that 70% of the immune system resides in the gut should underline the importance of maintaining acid-alkaline harmony.

There are, of course, various healthy pH ranges for different components of the body, from your mouth to your blood to your gut.

When pH levels get out of balance, gut-reliant processes such as digestion and nutrient absorption suffer.

One of the benefits of both pro and prebiotics is that they help to lower intestinal pH, ensuring an environment hospitable to friendly flora and inhospitable to harmful flora.

Electrolytes – essential minerals such as calcium, magnesium, potassium, chloride and sodium – also play a role, since dysbiosis causes impaired electrolyte absorption. This can lead to dangerously low stomach acid, another well-known cause of leaky gut.

Without sufficient electrolytes we will never achieve proper hydration of the gut, which is critically important for bowel function.

An electrolyte supplement such as Progurt Chloride can help. The liquid mineral formula contains four highly absorbable mineral chlorides, comprising magnesium, potassium, calcium and sodium. The electrolytes are provided in proper ratios to ensure optimal replenishment.

• Body Temperature

The link between between large-scale geography and human gut microbial composition was examined in a 2014 study, and climate was suggested as one reason why the ratio of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes varied widely between populations.

Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, incidentally, represent 99% of bacteria in the gut.

| “Firmicutes are notoriously good at helping the body extract more calories from food and aiding in the uptake of fats, hence their association with weight gain when they dominate in the gut.” – Dr. David Perlmutter |

“Bacteroidetes, on the other hand, don’t have this same capacity,” adds Dr. Perlmutter, in his book Brain Maker. “So the pattern of higher levels of Firmicutes and lower levels of Baceroidetes is associated with a greater risk of obesity.”

In simple terms, people who live in colder climates exhibit different microbial compositions to those in sunnier climes. This may be partly explained by the groups’ dietary habits, but the weather – which has a big impact on body temperature – is a key factor.

In a separate study on mice by Mirko Trajkovski of the University of Geneva, gut bacteria were shown to respond to the cold by making intestines better able to absorb nutrients.

Indeed, mice exposed to the cold became 50% more efficient at absorbing nutrients from food than mice living in warm conditions. However, after burning stored fat reserves in order to stay warm, the mice actually began to gain weight, with researchers finding a lack of bacteria in their guts consistent with obese people.

Thermoregulation, in other words, is closely associated with resident microbes. Spending time outdoors will help to increase microbial diversity by exposing you to various species, reducing your stress levels and – when the sun is out – contributing to body temperature.

While body temperature varies by person, age, activity etc, and microbial species proliferate over a wide range, bacteria from the human gut are said to grow well at the ideal core body temperature of 37 C.

This is one problem with ingesting probiotic bacteria harvested from bovine sources (i.e. cows): bovine animals have a body temperature a few degrees higher than humans, and thus their native bacteria intuitively thrives at a different temperature.

To add another layer of complexity, a 2016 research paper published in the journal Gut Microbes estimated that “microbial metabolism in the human gut produces 61 kcal/h, which corresponds to approximately 70% of the total heat production of an average person at rest.”

In other words, while body temperature influences gut microbes, gut microbes help the body generate heat. The bi-directional relationship once again rears its head.

• Alcohol and Tobacco: How Bad Habits Inflame the Gut

Of all the lifestyle factors that affect the balance of flora in your gut, two of the worst – habits that can have a seriously detrimental impact – are alcohol and tobacco.

Alcohol has been shown to decrease beneficial gut bacteria, and binge drinking in particular promotes a rapid increase in bacteria toxins within the cell.

According to a paper published in the peer-reviewed journal Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, alcohol induces gut inflammation through multiple pathways “which in turn promotes broad-spectrum pathologies both inside and outside the GI tract.

“In fact, many alcohol-related disorders, including cancers, liver disease, and neurological pathologies, may be exacerbated or directly affected by this alcohol-induced gut inflammation.”

It’s worth stating that red wine in moderation can actually promote Bacteroides due to its polyphenol content.

As for smoking, it goes without saying that tobacco’s cancer-causing chemicals wreak havoc on the bowel. It’s also true that smokers are twice as likely as non-smokers to develop Crohn’s disease.

Unsurprisingly, smoking-induced alterations to the microbiome have been widely observed and the mechanisms underpinning this connection continue to be studied.

Other Factors and How to Positively Influence the Microbiome

These are not the only factors which affect gut health, incidentally: nutrient flow, blood parameters, body type, oxygenation, hydration (water keeps intestines smooth and flexible), ethnicity and genetics also play a part, to some degree.

Clearly the decisions we make on a daily basis play a significant role in determining the status of our microbiome. Think about these factors the next time you’re suffering from bloating or gas, or sensing a disruption at gut level.

As for how you nurture a healthier gut, take each of the above bullet points in turn and ask what you can do to improve.

Of course, you can do nothing about the method of your birth or whether or not you were breastfed; but you can address factors such as diet, fitness, oxygenation, body pH, temperature and alcohol intake.

There are so many modes of behaviour which will have a positive effect on your gut, and consequently your overall health.

For example, an acute change in your diet — such as adopting plant-based – can alter your microbial composition within just 24 hours. Species that thrive on the food we eat can proliferate extremely quickly.

As indicated by the 2018 Cell study, “humans feature a person-specific gut mucosal colonization resistance to probiotics.”

In other words, once you get the conditions right, the efficacy of probiotics will be maximised.

How Can Probiotics Help You Maintain or Regain Health?

As we know, probiotics are ‘live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host’ and whether in the form of food or supplements, they have a great many duties in keeping us healthy.

Not only do probiotics encourage healthy digestion and absorption, including by facilitating the breakdown of indigestible complex polysaccharides, but they also produce B vitamins and certain enzymes.

What’s more, probiotics are essential to the production of nutritional components such as vitamin K, which is responsible for blood clotting, bone health and vitamin D utilisation, and essential amino acids.

Microbes also generate valuable metabolic byproducts from dietary components left undigested by the small intestine, and they even catabolise dietary carcinogens.

Other key functions of ‘beneficial’ bacteria include suppressing harmful bacteria, breaking down environmental toxins and pharmaceuticals, preventing your gut wall from becoming leaky, supporting enteric nerve function and priming the immune system to recognise self (body cells) versus non-self (foreign materials/antigens).

Prebiotics: Beneficial for Both Young People and Old

Prebiotics are non-digestible food ingredients which help to promote existing good bacteria by feeding and enriching beneficial microbes within the colon.

Prebiotics go a long way towards maintaining the homeostasis of the gut ecosystem and generally comprise complex carbohydrates such as galacto- and fructo-oligosaccharides, and inulin.

| “Almost nothing influences our gut bacteria as much as the food we eat. Prebiotics are the most powerful tool at our disposal if we want to support our good bacteria.” – Gut: The Inside Story of Our Body’s Most Underrated Organ |

As well as helping to reduce bacterial translocation (the passage of viable bacteria from the GI tract to the liver, kidney, blood etc) and improve gut mucosal immune responses, prebiotics have been shown to help prevent the development of atopic dermatitis in children and positively modulate the immune systems of elderly people.

According to one study from Japan, relatively small doses of prebiotics could increase our production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) by ‘switching on’ the metabolism of colonic microbiota.

One of the best-known forms of prebiotic is the aforementioned Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMOs).

Taken together, probiotics and prebiotics are known as ‘synbiotics’. While you can enjoy benefit from taking one or the other, it is considered optimal to ensure a ready supply of both.

Prebiotics actually help probiotic microorganisms “acquire higher tolerance to environmental conditions, including oxygenation, pH, and temperature in the intestine of a particular organism” according to a 2017 study in the journal Nutrients.

By keeping your friendly bacteria well-fed, you’ll better enable them to perform their useful functions.

The Role of Lactoferrin, a Natural Immune Modulator

Synbiotics aren’t the only form of gut health supplement. Another is lactoferrin.

Found in mammalian breast milk and amniotic fluid, this iron-binding glycoprotein protects us from harmful microbes.

One of the ways it does so is by limiting the availability of iron to pathogenic bacteria, which crave an iron-rich environment to proliferate.

At the same time, lactoferrin helps the body better absorb iron from food – hence why medicinal lactoferrin is commonly recommended to correct iron deficiency.

Antifungal, antiparasitic and antiviral, lactoferrin is one of the essential components of colostrum (the ‘first milk’) and is critical to supporting the intestines of infants at birth.

In fact, lactoferrin in colostrum is around seven times as abundant as that found in milk produced later.

By supporting the growth of beneficial Bifidobacteria, and exerting changes on white blood cells by increasing macrophage activity, lactoferrin helps to immunise breast-fed babies against bacterial infections and viruses.

It also acts as a bone growth regulator in the initial stages of skeletal development. As if that wasn’t enough, lactoferrin has antioxidant and anti-carcinogenic properties.

Lactoferrin supplementation is best combined with high-quality probiotics, as the pair work very much in synergy.

Both bovine and human lactoferrin have been shown to stop the growth of fungi in human cell cultures, and in fact bovine lactoferrin proved more efficient than human lactoferrin in halting the herpes virus in human cell culture.

Progurt’s Immuno Protein contains colostrum sourced from Australian and New Zealand dairy milk, protected by a vegetarian-friendly enteric coating. Effective for reducing skin conditions, the natural prebiotic agent is a great addition your gut-care regime.

What Should I Eat for a Healthy Gut?

We touched previously on the role of fibre, and certainly fibre is something you want to prioritise if you’re interested in nurturing your intestinal bacteria.

The insoluble fibre your gut bugs love comes from foods such as nuts, kidney beans and cauliflower and whole-wheat flour.

If you want to swap out the latter, you can replace with coconut flour or ground almonds/flaxseeds.

Fermented foods are also very beneficial, as they are brimming with live cultures. From kombucha, kefir and kimchi to live-cultured yogurt, tempeh and sauerkraut, these are worth consuming on a regular basis.

Be aware, however, that some options in the supermarket come with an array of added ingredients including preservatives and sugar. Some store-bought sauerkrauts are also pasteurised, and the heat kills off the probiotics.

| “Eat the rainbow. Remember, each plant food contains varying fibres that support different microbes, so getting a variety can help support a healthier gut microbiota.” – Hannah D. Holscher |

As mentioned earlier, you’ll want to avoid sugar altogether if you can; add pro-inflammatory processed vegetable oils to the Banned list and reduce your intake of grains and carbohydrates, many of which are high in microbiome-damaging gluten. Cook with butter, extra-virgin olive oil or coconut oil.

Eating a high-fibre diet replete with seasonable vegetables and fruits, plus sensibly reared meat, is the best thing you can do. Going entirely plant-based can also work, so long as you’re taking care to get the nutrients you miss out on.

Broccoli, dandelion greens and Jerusalem artichoke are some of the most gut-friendly foods on Earth.

Factors You Must Consider When Trying to Improve Gut Health

The gut is part of a complex and integrated system, in which microorganisms affect metabolism, immunity, skin, bones and stress.

Modify the bacterial population and the effects predictably ripple outward, but in order to successfully ensure that change takes place, we must provide a proper environment for the probiotic bacteria to survive and thrive.

So what’s missing from the current approach to gut health?

For one, many probiotic supplement manufacturers underestimate the sheer difficulty live bacteria face when they’re ingested.

As explained in The Good Gut, “The life of a microbe is not easy. First they need to withstand the acid bath that is our stomach and then ultimately find shelter in the dark, damp cavern of the colon, which is inhabited by more than a thousand different species.

“While food periodically arrives in the cave, competition for resources within the gut is fierce and survival depends on snatching what you can before others get their microbial hands on it.”

Given this inhospitable environment, there are three primary probiotic considerations worth making.

• Strength of Probiotics: Yes, Stronger Really is Better

It’s worth restating that probiotic definition: probiotics are live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host.

That middle section – when administered in adequate amounts – is an instructive caveat. It’s certainly one with which we wholeheartedly agree.

In order for live bacteria to confer a benefit, they must be suitably powerful. Powerful enough to withstand the aforementioned ‘acid bath’ of our stomach and gain a foothold in the intestinal tract.

Most probiotic supplements do not provide adequate amounts; on the contrary, they represent a drop in the ocean. What is one or ten billion Colony-Forming Units of live bacteria likely to achieve in the face of tens of trillions of highly competitive resident bacteria?

The introduced microbes will almost certainly be swamped. No foothold. No colonisation. No long or perhaps even short-term benefit.

If you are severely dehydrated, you do not drink a thimbleful of water. The same principle applies to correcting gut dysbiosis. A significant volume of probiotic bacteria is required to stimulate meaningful changes to the microbiome and restore harmony.

This was born out by the 2018 Israeli study, which showed that after administration with a daily probiotic containing 5 billion Colony-Forming Units, the microbes either passed right through the volunteers or briefly lingered before being crowded out by highly competitive existing microbes.

A 2019 study comparing the efficacy of a 7 billion CFU probiotic versus a 70 billion probiotic showed a similar result: participants who ingested the higher dose enjoyed “higher, earlier and longer recovery of the probiotics in their feces.”

• Source: Choose Human Bacteria, Not Bovine

As mentioned earlier, the overwhelming majority of probiotic supplements contain bacteria harvested from cows, which have a different body temperature from humans. Some also contain bacteria from soil. Needless to say, neither is intuitive to the human gut.

Although a number of non-human probiotic strains have proven effective in clinical trials, supplementing with human bacteria which are capable of surviving stomach acid, and are intuitive to the gut lining and human body temperature, is clearly the best and most natural course of action.

• Gut Environment: Set the Stage for Effective Colonisation

The gut environment is dependent upon all of the aforementioned factors: method of birth, diet, hydration level, exercise status, antibiotic usage etc.

Based on these factors, the environment will be receptive or resistant to the colonisation of bacteria introduced via supplements. (It might also be somewhere in between.)

As mentioned, there are many steps you can take to improve gut environment and increase the likelihood of probiotic colonisation.

As noted in the 2018 study, “gut mucosal colonisation is highly dependent on the capacity of probiotics to interact with locally-entrenched microbiome niches.”

High Strength, Human Probiotics from Progurt

With these three factors in mind, Progurt is the supplement you want to be looking at. Not only does it contain an enormous quantity of beneficial bacteria, but just as important, the bacteria is entirely human-derived.

That is to say, 100% native and natural to the human gut, having co-evolved with us over millennia. While even probiotics marketed as high-strength provide 50 or 100 billion live bacteria, Progurt supplies a cool one trillion. It is the only probiotic currently on the market to offer such a powerful dose.

Bacterial species, meanwhile, comprise multiple synergistic strains which are commonly missing and fragile in the population. These include Lactobacillus Acidophilus, Lactobacillus Bifidus and Streptococcus Thermophilus.

All strains were identified, isolated and ‘banked’ in the recent past, at a time when they were much more plentiful than they are now. Again, these are native strains derived from a healthy human source.

| “What we’re talking about is replacing gut bacteria you were born with, that have either been missing from your gut or suppressed or diminished, and trying to restore the colonisation of those strains.” – Robert Beson, Progurt Founder |

Unlike most probiotics, Progurt does not come in a capsule form with enteric coating but as a freeze-dried powder; simply disperse the sachet in water then drink: the beneficial bacteria will begin to replicate in the mouth and migrate between the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract.

It is the temperature of the human body which activates the freeze-dried dormant bacteria, bringing it to life the same way an incubator activates bacteria in milk.

To be clear, you cannot find this blend of strains in any other probiotic supplement. It’s little wonder Progurt has garnered hundreds of five-star customer reviews, with users reporting a major difference not only for gut health but numerous other body systems.

Boost Your Gut and Change Your Life

Hopefully we have demonstrated that the maintenance of a healthy gut microbiome is absolutely critical to human health, and that the integrated picture is much more complex than many suppose.

That the gut is increasingly viewed as the true seat of health is unsurprising in light of the growing evidence. If you were born via C-section, fed infant formula instead of breastmilk, have consumed antibiotics, eat a nutrient-starved diet or have been exposed to persistent stress, getting your gut right is one of the best things you can do.

Use this article as a guide and make the necessary changes: you’ll be stunned by how much better you feel after correcting dysbiosis and restoring harmony.

Water for Health Ltd began trading in 2007 with the goal of positively affecting the lives of many. We still retain that mission because we believe that proper hydration and nutrition can make a massive difference to people’s health and quality of life. Click here to find out more.

Leave a comment