The Strathspey water dispute looks set to rumble on, after hundreds of residents called for a full-scale review into the safety of water chloramination. The quality of tap water in both Strathspey and Badenoch has come into question ever since Scottish Water opened a £24 million treatment works at Aviemore in 2012 and began taking supplies from a subterranean aquifer. Previously, the source had been Loch Einich in the Cairngorms.

Residents Petition Parliament on Water Quality

Access to clean drinking water is about as enshrined a right as we have in the United Kingdom. However, the mains supply in the Cairngorms National Park is now steadfastly avoided by many. This was after Scottish Water admitted that a small number of customers had found chlorine levels ‘not to their taste.’ The taste and smell of the water, specifically, have been criticised.

Last Thursday, May 25, Caroline Hayes and Kincraig community councillor Lesley Dudgeon presented a petition signed by hundreds of disgruntled residents to the Scottish Parliament’s public petitions committee, calling for a review. The committee has now agreed to liaise with both the Scottish Government and Scottish Water, scrutinise water quality regulation and green-light independent research into the chloramination of drinking water not just in Strathspey, but throughout the country.

Alarmingly, residents in Strathspey and Badenoch have alleged that water from the mains supply is causing an outbreak of skin complaints – and many have resorted to drinking only bottled water. The NHS Highland health board have recently agreed to review additional health data in an effort to clarify the matter.

What is Chloramination?

Chloramination is a means of water treatment that has gained popularity in recent years. Chloramines are combinations of chlorine and ammonia (in small quantities) which are added to the water to kill potentially harmful bacteria. The chloramination process was completed at Aviemore at the start of April.

According to a 2016 Water Quality Report by the Schererville Water Department in Indiana: ‘Although chloramination is a very effective means of water treatment, it can be toxic when introduced directly into the bloodstream.’ Of course, there is no suggestion that chloramines have entered the bloodstream of residents in the Cairngorms.

One vocal critic of chloramination is well-known environmental campaigner Erin Brocovich, who called Scottish Water’s new process a dirty trick. ‘Adding ammonia to drinking water does not improve it,’ she said. ‘It masks the underlying problems and contaminants. It adds additional chemicals and creates more reactions that are in fact more toxic.’

Djanette Khiari, Research Manager at the Water Research Foundation, echoes those concerns: ‘Chloramination can be a complex process and improper management can lead to unintended consequences including nitrification, formation of non-regulated DBPs and deleterious effects on some elastomeric materials used in the distribution system… Water professionals need to understand the various aspects of chloramination with the goal to better manage and operate their systems and minimise unintended consequences.’

The Link Between Chloramines and N-nitrosamines

In a forthcoming peer-reviewed paper to be published in the June edition of the American Water Works Association (AWWA) journal, Kathryn Linge – a senior research fellow at the Curtin Water Quality Research Centre, part of Western Australia’s Curtin University – assesses the effects of chloramination and chlorination.

Linge and her fellow researchers have specifically investigated the effects of both water treatment methods on the formation of N-nitrosamines – chemical compounds which have been reported to be carcinogenic, mutagenic and/or teratogenic.

The team found that all measured N-nitrosamines, excluding N-nitrosodipropylamine, were detected at least once, and total N-nitrosamine formation ‘was higher after chloramination than after chlorination.’ The authors found that NDMA formation was always higher in chloramination experiments.

NDMA – N-nitrosodimethylamine – is a probable human carcinogen according to the US Environmental Protection Agency’s Integrated Risk Information System. NDMA is the most common N-nitrosamine detected in drinking water. In the past, rubber materials used in water pipelines have been cited as being responsible for the formation of NDMA in chloraminated drinking water distribution systems. NDMA and other N-nitrosamines have also been found to leach from latex gloves.

In a recent review of NDMA concentration in 38 Australian drinking water systems, the formation of NDMA was shown to be limited to a few specific treatment plants: the primary factors leading to NDMA detection were the chloramination process and the use of poly-DADMAC as a coagulant aid.

What Next for Strathspey Water?

Evidently the concerns of residents must be assuaged, and the public petitions committee is now in the process of contacting various organisations in an attempt to do just that.

Scottish Water, meanwhile, has assured residents that Strathspey water is fully compliant with required standards; it has also defended the process of chloramination.

In the meantime, many people in the local area are continuing to hydrate by drinking bottled water. Nethy Bridge farmer John Kirk even claims his cattle turn their noses up at the local tap water, so it’s not hard to see why people are resorting to this.

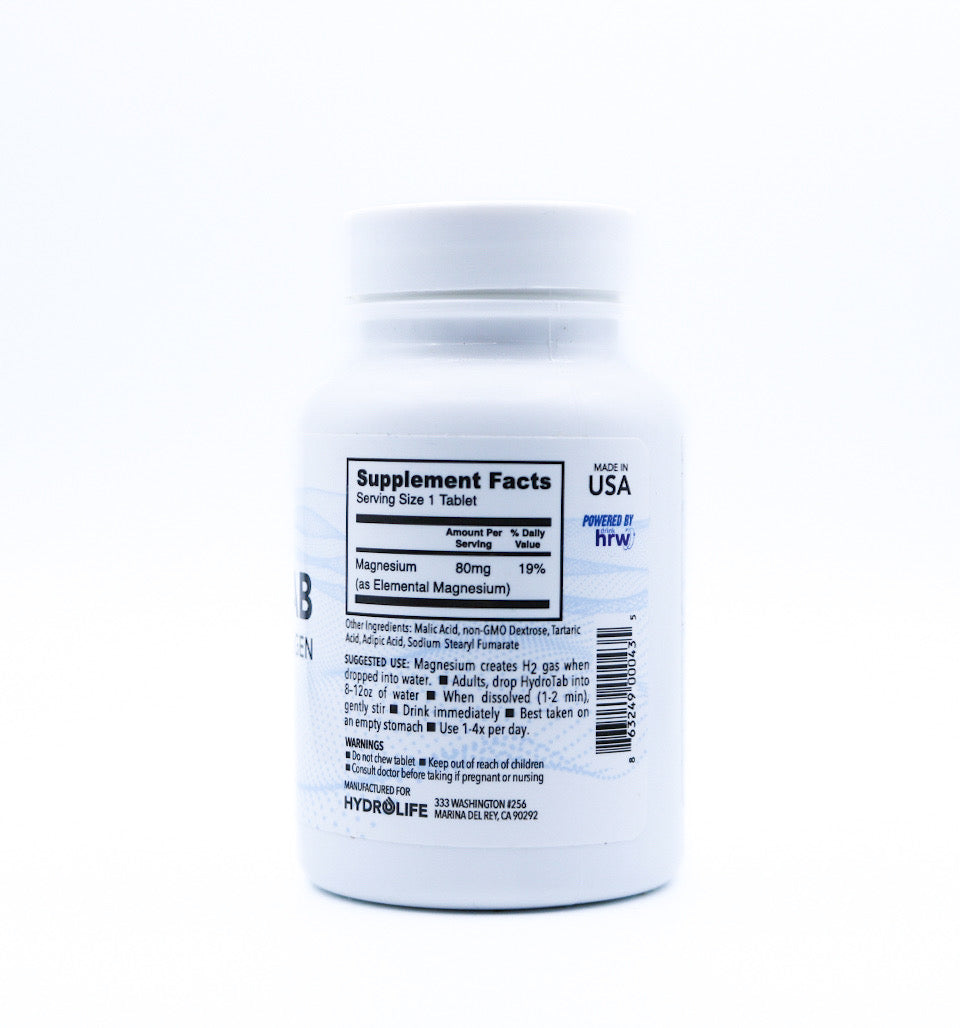

Instead of buying bottled water by the caseload, denizens of the areas affected might consider investing in a good quality point-of-sale water filter which removes chloramines and other potentially dangerous chemical contaminants from the mains supply.

One hopes the Badenoch and Strathspey water dispute can be resolved in the near future. It will be interesting to see whether the Scottish Parliament committee can satisfy Caroline Hayes, Lesley Dudgeon and the other angry residents, who are learning that satisfactory tap water should never be taken for granted.

Leave a comment