Although you can’t see it, your microbiome is integral to human physiology, health, and disease (Pray 2013). It is arguably the most intimate connection between humans and their external environment, mostly because what we eat is so important.

The potential for disease increases when the microbiome is negatively affected. Sometimes even the smallest complaint from our body is a sign that our microbiome is off.

The following is a list of health implications to watch out for that may have started with a disturbed microbiome.

1) Autoimmune Disorders

Persons with autoimmune disorders have intracellular microbes that slow innate immune defenses by dysregulating the vitamin D nuclear receptor, which allows pathogens to accumulate in tissue and blood. Further dysfunction occurs when molecular mimicry between pathogen and host interfere with protein interactions. In response to these pathogens, autoantibodies may be created.

Autoimmunity results from the successive accumulation of pathogens into the microbiome over time, and the ability of such pathogens to dysregulate gene transcription, translation, and human metabolic processes. Autoimmune disorders may also be genetic because of the inheritance of a familial microbiome.

Medical professions may treat autoimmunity by initiating immune defenses and targeting pathogens, but the death of cells results in immunopathology (Proal 2013).

2) Mental Health Disorders

Normal gut microbiota may affect normal brain development and behavioral functions (Heijtz et al, 2010). One possible reason is because gut microbiota can elicit signals via the vagal nerve to the brain and vice versa.

Modulation of transmitters within the gut, such as serotonin, melatonin, gamma-aminobutyric acid, histamines, and acetylcholine, could also mediate the effects of the gut microbiota.

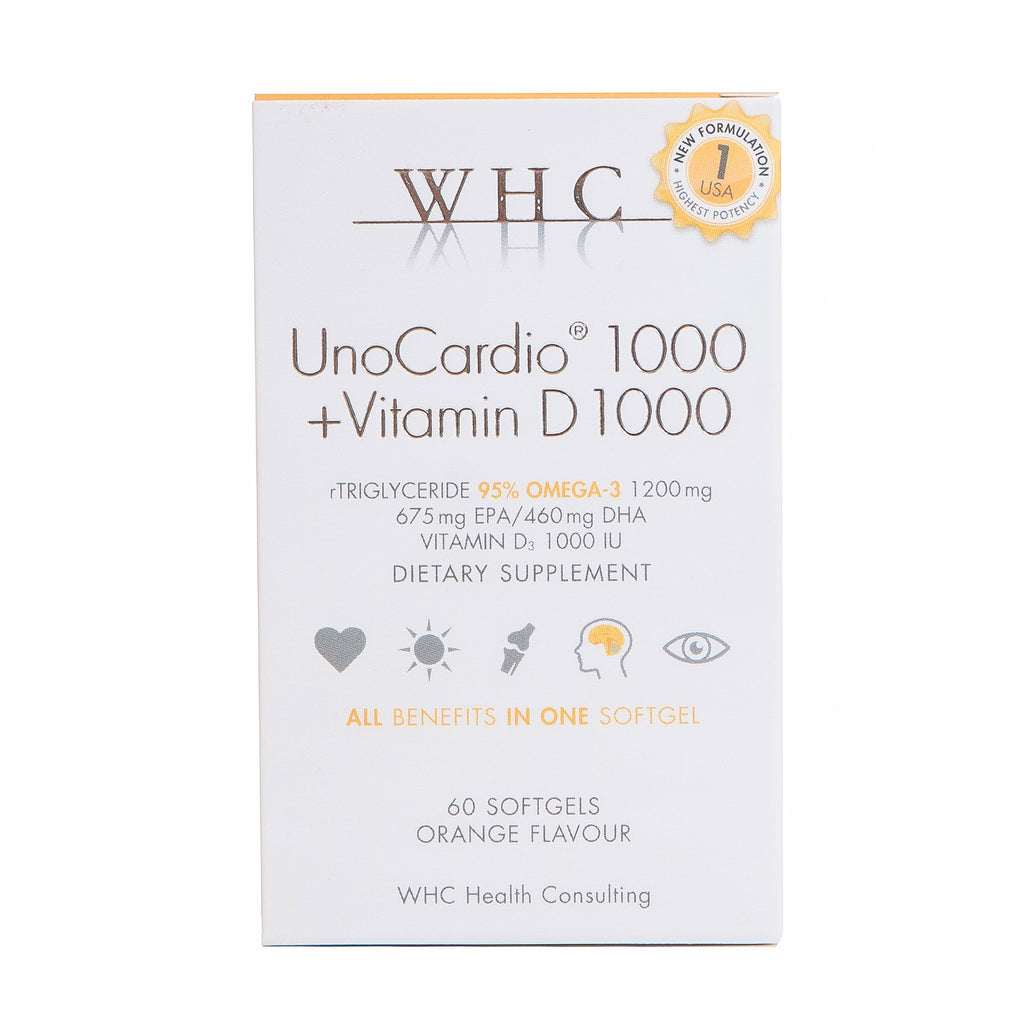

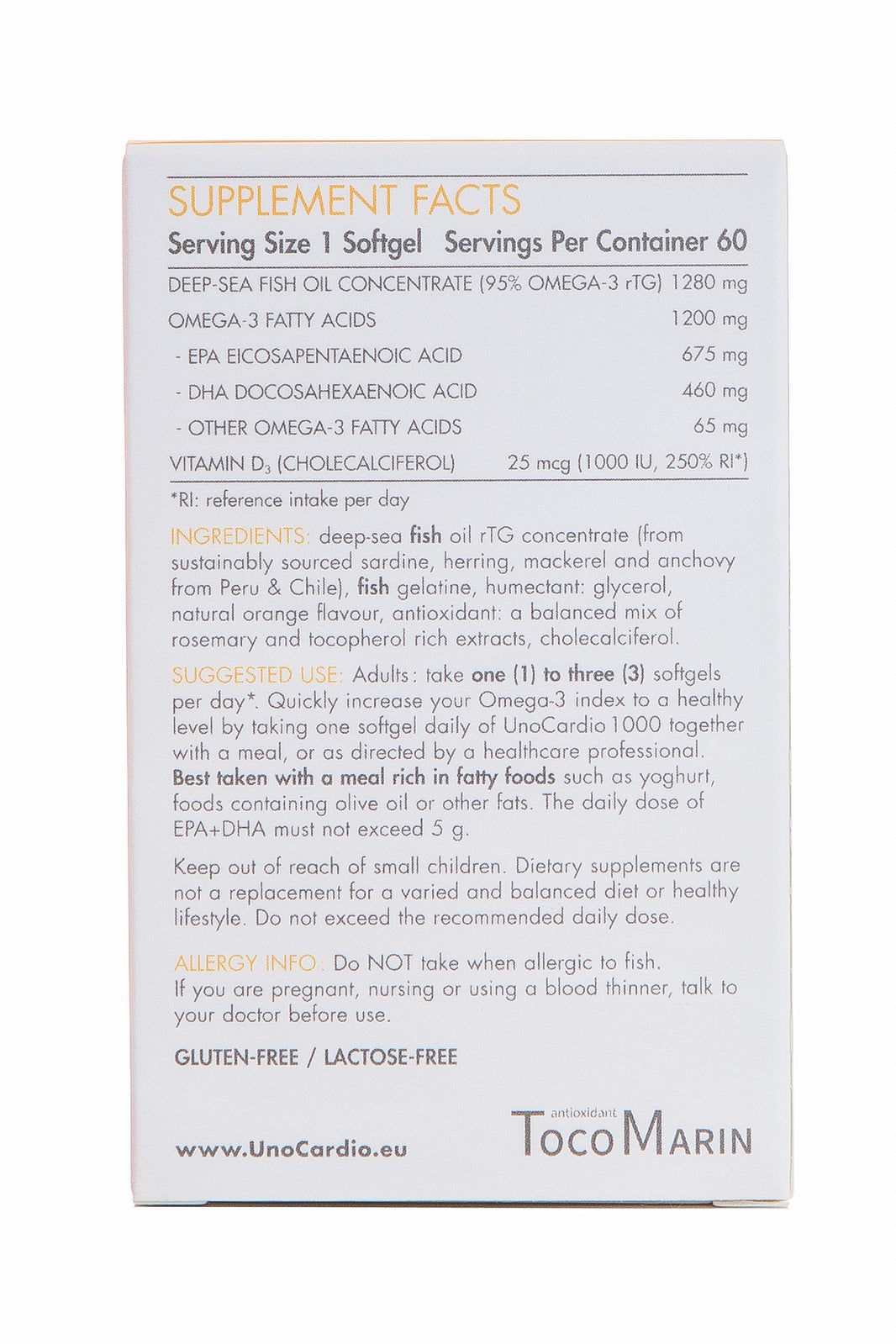

3) Heart Disease

Research has indicated that there is an important connection between the diet, the microbiome, and cardiovascular disease. Dietary carnitine (found in red meat) and lecithin are shown to be metabolized by gut microbes to trimethylamine, which is metabolized by the liver.

High levels of trimethylamine-N-oxide, or TMAO, in the blood strongly correlate with CVD and associated acute clinical events.

Research suggests that that presence of specific, yet unidentified microorganisms in the gut that are linked to diet may be required for high TMAO levels, which is responsible for cardiovascular disease progression (Mendelsohn & Larrick, 2013).

4) Obesity

The composition of the gut microbiome plays an important role in regulating body weight. Data from research mentioned in Devaraj et al, 2013 studied the fecal gut microbiota in 12 obese individuals who participated in a weight-loss program for a year by following either a fat-restricted or carbohydrate-restricted low-calorie diet. Results confirmed that alterations in gut microbial composition are associated with obesity.

A second study conducted on children from birth to age 7 years old documented an abundance of Bifidobacterium taxa and decreased proportions of Staphylococcus aureus in children whose weight was within reference intervals at age 7 years than in those who were overweight or obese.

5) Diabetes

Increased amounts of toll like receptors, or TLRs, are present in patients with obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome (Devaraj et al, 2013). TLRs are pattern recognition receptors that are important for mediating inflammation and immunity.

An animal study mentioned in Devaraj et al, 2013 demonstrated that mice deficient in the microbial pattern-recognition receptor TLR5 displayed hyperphagia, became obese, and developed features of the metabolic syndrome, including hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and insulin resistance secondary to dysregulation of interleukin signaling. When gut microbiomes from these mice were transplanted into germ-free mice with an intact toll-like receptor 5 gene, the mice developed similar features of the metabolic syndrome, which suggests that intestinal microbiome was the key determinant of this disease phenotype.

6) Cancer

Pathogens, such as viruses, promote cancer by genetic mechanisms. Other pathogens promote cancer through inflammation, which contributes to carcinogenesis. However, research suggests that human disease is attributable not only to single pathogens but also to global changes in our microbiome.

Studies in germ-free animals showed evidence for tumor promoting effects of the microbiota in spontaneous, genetically-induced and carcinogen-induced cancers in various organs, including the skin, colon, liver, breast and lungs. Also, depletion of the intestinal bacterial microbiota in mice, using antibiotics, reduced the development of cancer in the liver and the colon, as does the eradication of specific pathogens in humans and in mice (Schwabe & Jobin, 2013).

Other Health Concerns Associated with the Microbiome

Other health problems that may be affected by the microbiome include sinus infections, digestive disorders, immune problems, asthma, acid reflux, constipation, diarrhea, and skin conditions. Balancing your microbiome may be as simple as cleaning up your diet, getting enough sleep, and finding time to exercise.

References

Devaraj, S., Hemarajata, P., & Versalovic, J. (2013). The Human Gut Microbiome and Body Metabolism: Implications for Obesity and Diabetes. Clinical Chemistry, 617-628. Heijtz, R., Wang, S., Anuar, F., Qian, Y., Bjorkholm, B., Samuelsson, A., ... Pettersson, S. (2010). Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 3047-3052. Mendelsohn, A., & Larrick, J. (2013). Dietary Modification of the Microbiome Affects Risk for Cardiovascular Disease. Rejuvenation Research, 241-244. Pray, L. (2013). The human microbiome, diet, and health: Workshop summary. National Academies Press. Proal, A., Albert, P., & Marshall, T. (2013). The human microbiome and autoimmunity. Current Opinion in Rheumatology, 234-240. Schwabe, R., & Jobin, C. (2013). The microbiome and cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer, 800-812.

Leave a comment