A new global study has correlated high consumption of dietary fats with a reduced risk of death and stroke.

In direct opposition to those who insist we should avoid saturated fats like the plague, scientists confirmed that cutting sat fats so they made up less than 3% of our total calories, actually increased death rates by 13%.

So what’s the story here? Who’s right? And should we steadfastly avoid fat or use it as a valuable energy source?

What the Study Says

The study in question was presented at last month’s European Society of Cardiology Congress in Barcelona. Led by Dr Mahshid Dehghan from Canada’s McMaster University, it investigated a global population of over 135,000 people in an attempt to determine dietary factors contributing to death rates.

As well as the aforementioned result for saturated fat reduction, scientists learned that eating more fat of all kinds reduced the overall risk of death by 23%; stroke risk by 18%; and non-heart related mortality by 30%.

The findings will be music to the ears of those in the field of nutrition who, rather than demonise fat, have long pointed the finger at refined carbohydrates when it comes to a multitude of negative health outcomes like obesity and diabetes.

Indeed, researchers found that diets high in carbs (77%) correlated with a 28% greater risk of mortality.

Should We Really Restrict Dietary Fat?

This is not the first time fat – and particularly saturated fat – has received good press. Indeed, many scientists, nutritionists and naturopathic doctors have been calling attention to the illegitimacy of saturated fat scaremongering for some time.

Several excellent books have been published on the subject, including Nina Teicholtz’s The Big Fat Surprise which came out a couple of years ago. Gary Taubes’ 2002 Times Magazine cover story What If It’s All Been a Big Fat Lie? was another early challenge to the conventional orthodoxy of restricting dietary fat.

And it’s not just those on the margins who refute the received ideas on saturated fats.

A recent meta-analysis published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, an offshoot off the BMJ, showed no association whatsoever between saturated fat consumption and all-cause mortality.

Nor was there any correlation for coronary heart disease, CHD mortality, ischaemic stroke or type-2 diabetes.

Despite this, the American Heart Association continues to state that nothing has changed: we should fear saturated fats, replacing them with unsaturated vegetable oils and spreads.

Public Health England agree, recommending that we eat no more than 30g of saturated fat per day.

It seems that these camps have bedded in for the long haul, unwilling to consider whether the guidance they are issuing may be wrong.

Amidst a deadlock that shows no signs of breaking, the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) reviewed all of the available evidence on saturated fat and published its findings in May 2018.

They reinforced the anti-sat fat dogma by recommending “no changes to current government advice.”

Good Fats, Bad Fats and Omegas

Is there such a thing as good fats and bad fats? Patently, yes. There is a clear link, for instance, between artificial trans fats and coronary heart disease. This is why the US Food and Drug Administration is in the process of eliminating partially hydrogenated oils (PHOs), the primary source of trans fats, from the food chain.

Made by pumping vegetable oils with hydrogen, trans fats are cheap to produce and benefit from a long shelf life. Found in everything from doughnuts and cakes to frozen pizza and margarines, trans fats increase bad cholesterol – without simultaneously raising good cholesterol – and negatively affect lipoproteins.

Numerous observational studies also tie trans fat consumption with a spike in heart disease risk.

As for good fats, we are circling back to rockier ground. Saturated fats are still deemed to be unhealthy, with the vegetable and processed oil industry in particular keen to support this view. After all, these industries will be the chief beneficiaries if we were all to suddenly jettison sat fats from our diet.

But does this tell the whole story What about the benefits of saturated fats, such as they are? In fact, there are quite a few. In order for calcium to be efficiently assimilated into our bones, at least half of dietary fats should be saturated.

Saturated fats like lauric and myristic acid also play an essential role in immune health, and eating SFAs actually reduces one’s levels of Lipoprotein(a), a causal risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Of course, SFAs aren’t the only type of fat – there’s monounsaturated and polyunsaturated too. The difference between them lies in the bond structure: saturated fats contain no double bonds while monounsaturated have one double bond and polyunsaturated have more than one.

The unique molecular structure of each fat affects how it behaves within the body.

While saturated fats comprise animal fats and tropical oils, monounsaturated derive from olive oil, nuts, whole milk and avocados. It is generally considered a good fat, proving effective against heart disease, insulin resistance and bone weakness.

Polyunsaturated fats, meanwhile, are made up of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. Like MUFAs, PUFAs have a solid reputation: they are known to reduce harmful LDL cholesterol and lower triglycerides while also offering protection for the heart and brain, benefits which stem mainly from the omega-3s.

Examples of omega-3 fats include oily fish and flaxseeds, while omega-6 is found in safflower, grapeseed and walnut oil.

Although polyunsaturated fats are considered healthy by many, it is vitally important to maintain a good balance of omega-6 to omega-3. Failing to do is associated with a number of dangerous effects, not least a steep rise in inflammation. This is because many omega-6s are pro-inflammatory, while omega-3s are anti-inflammatory.

Our ancestors are said to have followed a ratio of 1:1, and some of the healthiest populations in the world today (read: non-agricultural) maintain a similar score.

However, the modern Western diet contains far more omega-6 than omega-3: the oft-quoted figure is 16:1! We should continually strive to bring this back into balance.

Changing How We Look at Fats

The debate around dietary fats is sure to continue, possibly ad infinitum, but there are simple steps we can take to ensure we’re eating healthily.

Perhaps the single most important one is to avoid highly-processed fats in the form of processed seed and vegetable oils. We are instructed to avoid processed carbohydrates often enough, so why should the advice change when it comes to heavily-processed fats?!

Swerving industrially-processed, artificially manufactured and invariably inflammatory food is the true way to avoid ‘unhealthy’ fats and maintain a proper balance of omega-6 to omega-3. Crushing oil-bearing seeds and heating them to 200+ degrees has a demonstrably negative impact on the nutritional content of the end product.

Contrast this with the gentle processing method used to procure true olive oil – one which preserves the integrity of the beneficial fatty acids and antioxidants.

Conclusion

Eating plenty of omega-3 rich foods is another recommendation we would endorse: vegetarians should look to chia, flaxseed and unrefined flaxseed oil, while meat eaters should aim to consume a few portions of oily fish per week.

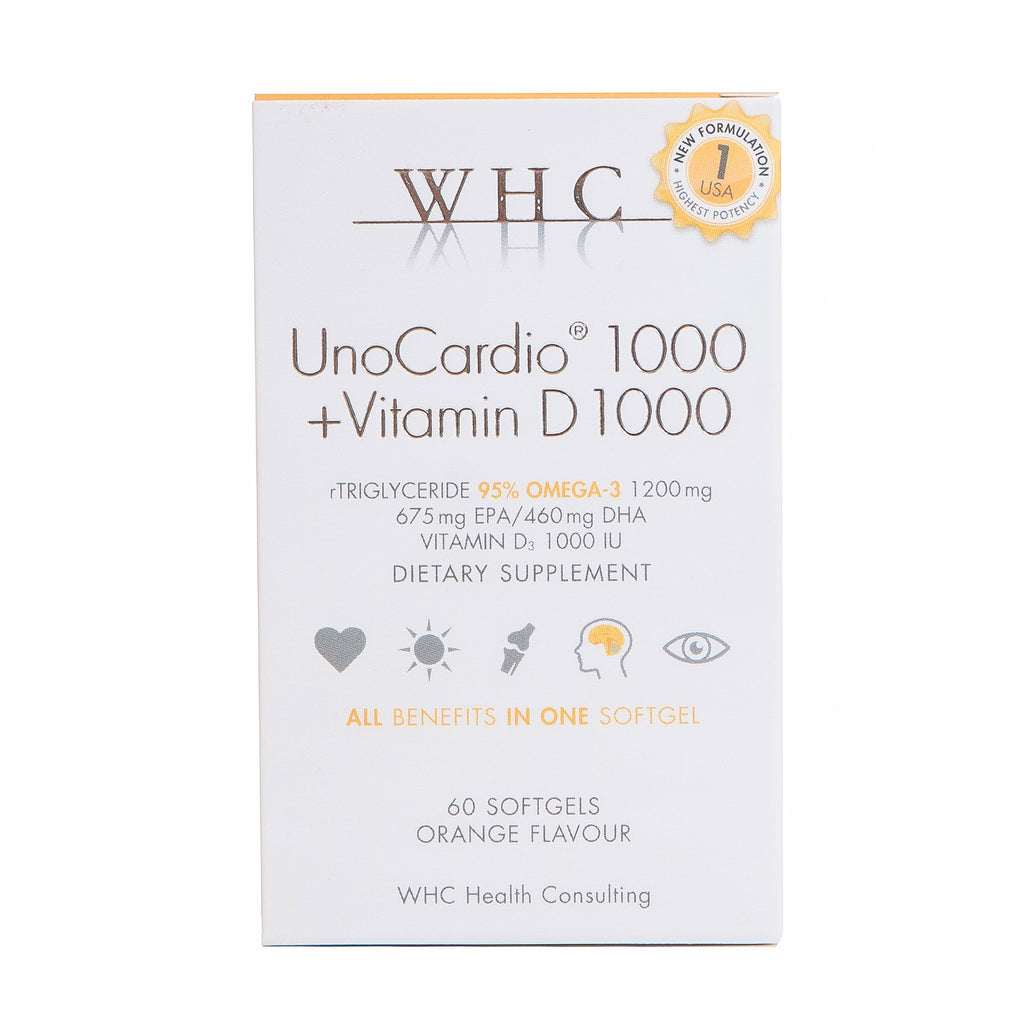

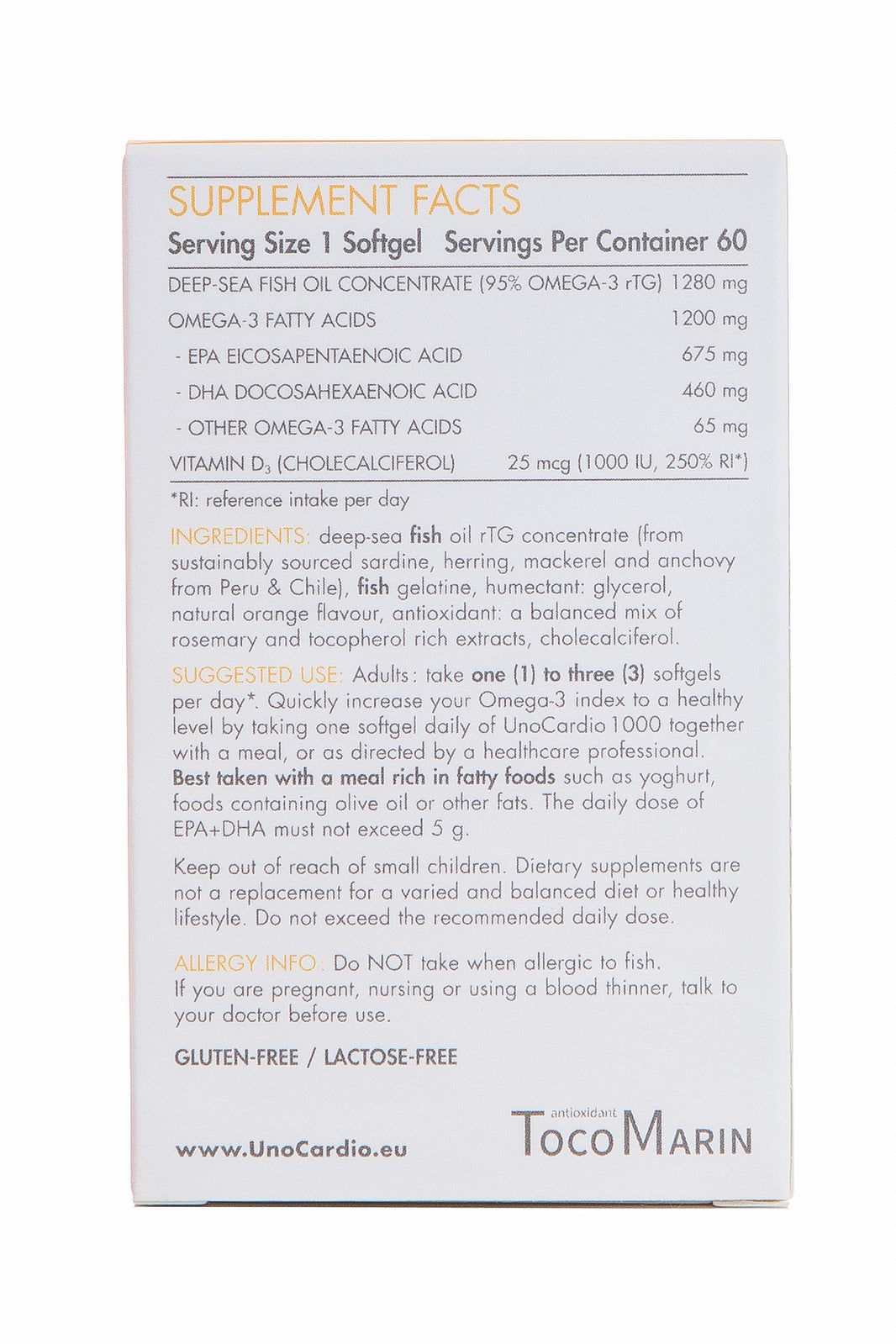

If needed, you can also supplement with a fish oil containing high amounts of omega-3 EPA and DHA.

The take-home: don’t view fat as the enemy. Eat natural and your body will thank you.

While we’ve got you here, you might be interested to read our article “5 Great Cooking Oils and Fats to Use on a Keto Diet.”

Water for Health Ltd began trading in 2007 with the goal of positively affecting the lives of many. We still retain that mission because we believe that proper hydration and nutrition can make a massive difference to people’s health and quality of life. Click here to find out more.

Leave a comment