Are we eating more, or less, of what we need to be eating? How have dietary habits changed, and what can we learn from the prevailing trends and patterns?

We can answer these questions by taking a look at the National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS), which analysed data spanning 2008-2017. Published in early 2019, the NDNS provides more than just a snapshot of a generation’s culinary mores.

So are we doing better or worse than we were in 2008? And what might the NDNS look like when it’s published in January 2029?

National Diet and Nutrition Survey: How It Works

The National Diet and Nutrition Survey is a continuous, cross-sectional survey jointly funded by Public Health England and the Food Standards Agency. So, yes, the data discussed herein is British: but as a template of western society, it makes for instructive reading.

The NDNS essentially collects quantitative information on the food consumption, nutrient intake and nutritional status of the UK population aged 1.5 years and over. The survey covers a representative sample of approximately 1,000 people every year.

Armed with evidence from the annual NDNS, Public Health England flag nutritional issues faced by the population and track progress towards achieving government health and nutrition objectives.

The need for regular appraisals of the nation’s nutritional status is self-evident. In 2016/17, there were 617,000 admissions to NHS hospitals in which obesity was a factor, an increase of 18% on the previous year.

Just over a quarter (26%) of adults are classified as obese, while the same percentage manage to eat the recommended five portions of fruit and vegetables per day (even though 10 portions is associated with the best health outcomes).

Nutrient-deficient diets, of course, are recognised as major contributory risk factors for poor health and mortality, with obesity considered a leading cause of cancer, heart disease and type 2 diabetes. So what were the results of the 9-year survey?

A Nation’s Nutrition

So what changes did the researchers witness over the 9-year study period in question? Well, to begin with, there was very little change in the intake of fruit and vegetables – this in spite of the authorities continually beating the drum about the importance of consuming five, seven or ten portions per day.

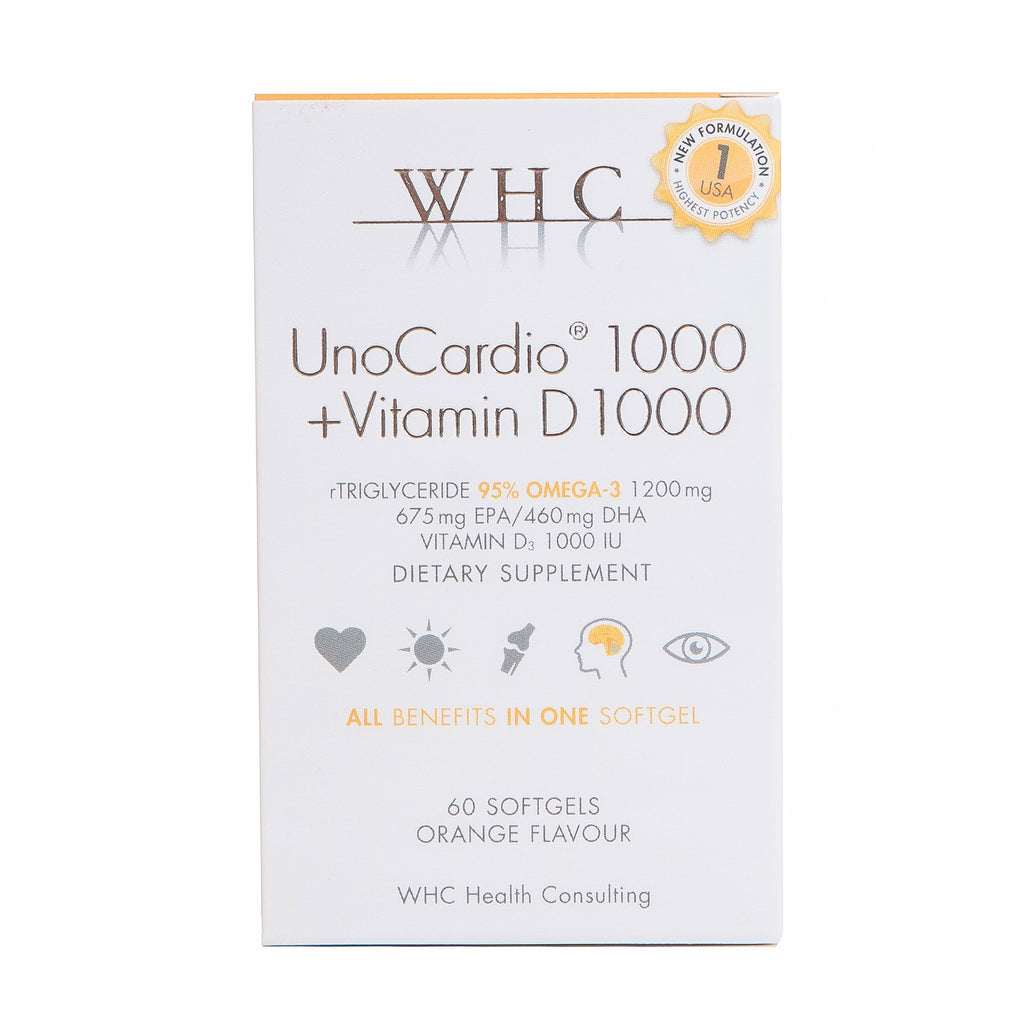

All mean age and sex groups had a mean intake below the five-a-day recommendation. There was little change, too, in the intake of oily fish – a grave disappointment as we continue to learn about the massive health benefits of omega-3 fatty acids.

Omega-3s are especially vital for brain health, heart health and vision, although they have also been shown to reduce osteoarthritis pain, keep gut bacteria in balance, treat inflammation and oxidative stress caused by pollution and reduce elevated cholesterol and blood pressure in older adults, among other things.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there’s been a downward trend in the intake of some vitamins and minerals. All groups exhibited a significant reduction in vitamin A and folate (vitamin B9) over the nine years; the average intake for girls aged 11 to 18 dropped and remained below the Recommended Daily Intake.

For females aged 11 to 18, and women aged 19 to 64, the proportion with intakes below even the Lower Reference Nutrient Intake (LRNI) rose by 9 and 6 percentage points respectively over the study period.

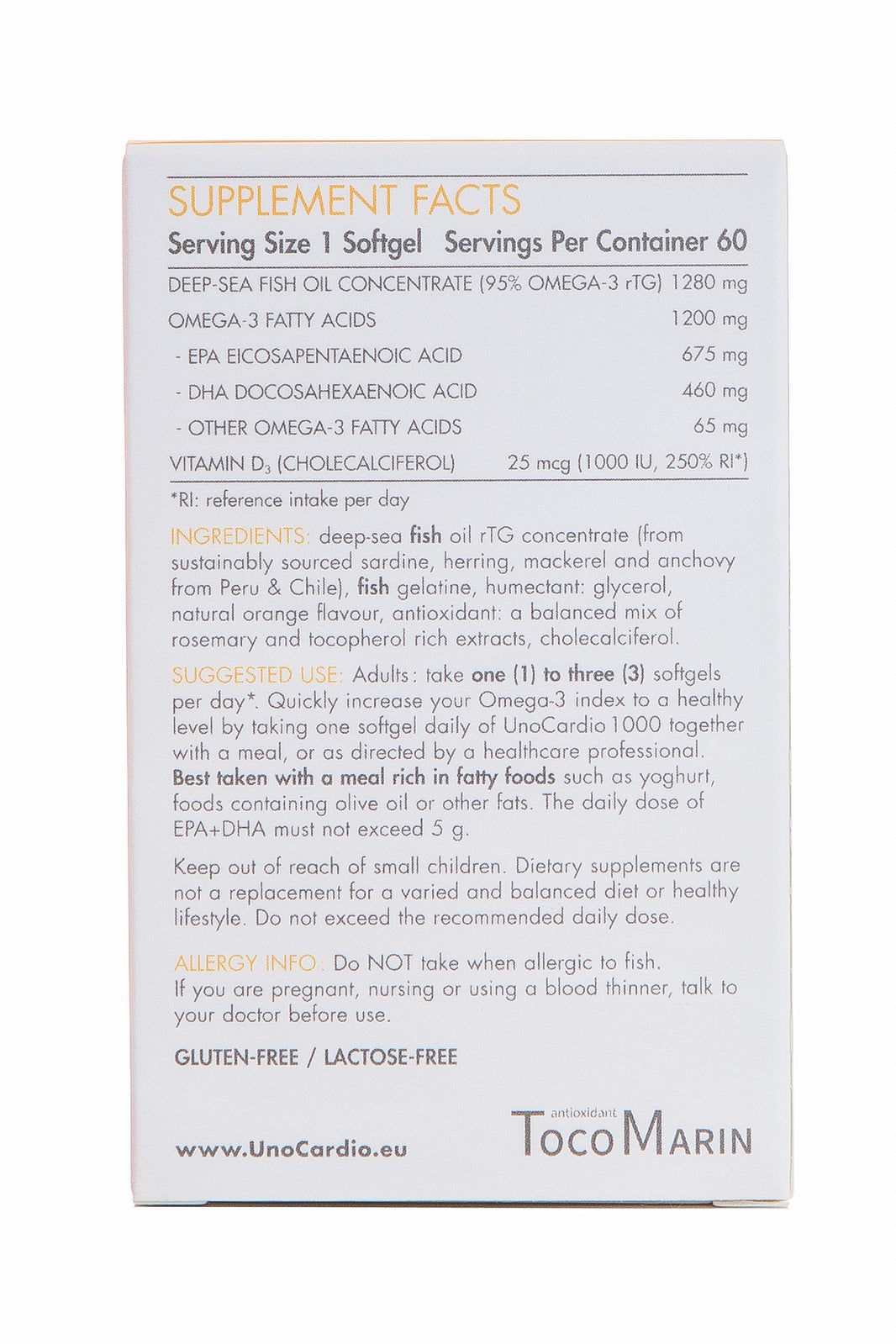

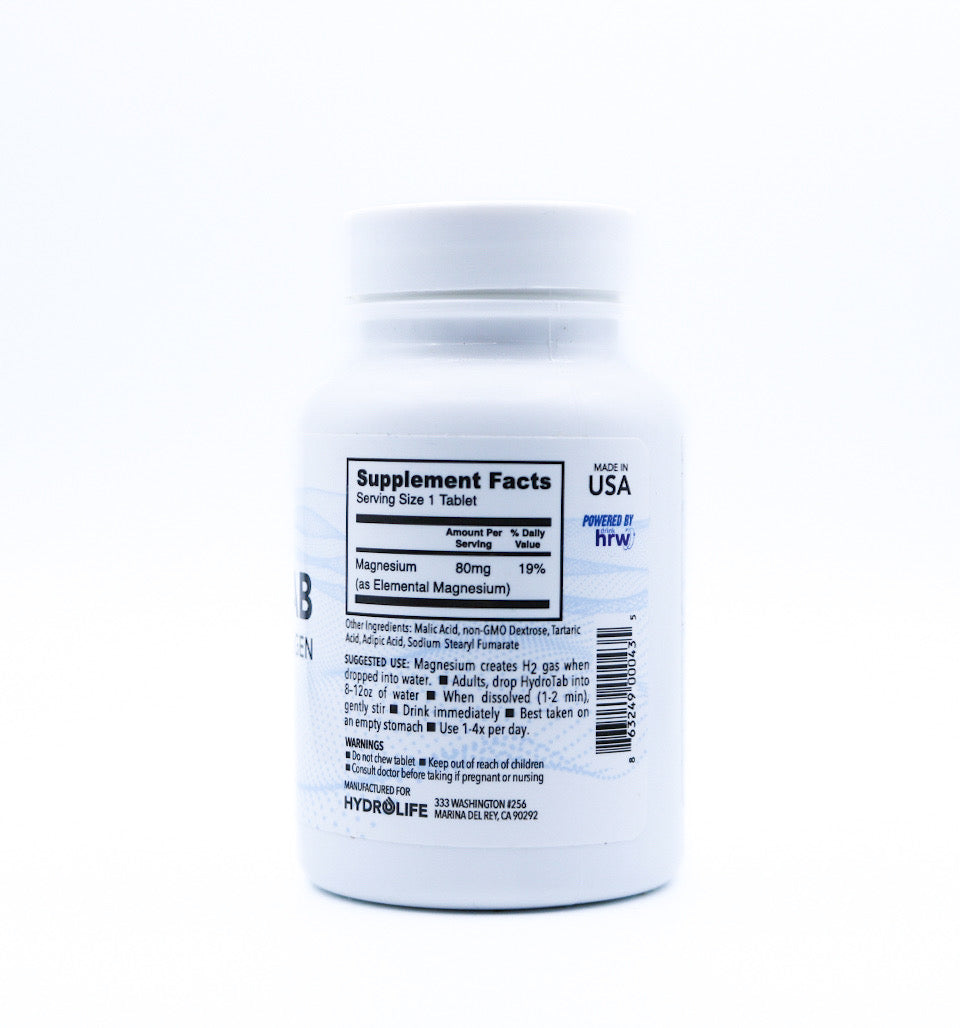

An average annual reduction in iron intake was also noted in most age/sex groups, with females in particularly affected. Iodine intake was down for most, as was magnesium, and children aged 1.5 to 10 were eating 10mg less bone-building calcium per day.

During the sun-starved months of January, February and March, 19% of children aged 4 to 10, 37% of children aged 11 to 18 years, and 29% of adults were shown to have vitamin D deficiency. It’s little wonder the British Medical Journal argue that more foods be fortified with the vitamin.

Although there was a significant decrease over time in sodium intake among all age/sex groups, it is worth asking whether that is in fact a good thing.

The results weren’t all negative: there was a downward linear trend in the intake of fruit juice among all age/sex groups. Indeed, the percentage of kids drinking sugar-sweetened soft drinks fell by 26, 35 and 17 percentage points for groups aged 1.5 to 3 years, 4 to 10 and 11 to 18, respectively. Dentists will be pleased with that pattern.

The intake of free sugars more generally has significantly decreased among children. As a percentage of total energy, free sugar intake fell by 2.7, 2.4 and 3.5 percentage points for youngsters in the aforementioned groups. Adults also showed a reduction, albeit more modest, in free sugar intake as a percentage of total energy over time.

Despite this positivity, average free sugar consumption among all age/sex groups still exceeds the official UK recommendation that no more than 5% of total energy come from free sugars.

Other pros to be taken from the study: intake of red and processed meat appears to be down; there’s been a significant reduction in the intake of trans fats; men aged 19-64 are eating 2.4g more fibre per day than they were nine years ago; and there’s been a downward trend across all age/sex groups, in the percentage of people consuming alcohol.

This latter trend was statistically significant for adults aged 19-64 and girls aged 11-18 years.

You can read the National Diet and Nutrition Survey report in full here.

Some Thoughts on the Eatwell Guide

We are all advised to follow a healthy, balanced diet as shown in the Eatwell Guide. In theory, following the Eatwell Guide is absolutely the best thing we can do in terms of our nutrition.

However, the Eatwell Guide is deeply flawed, with an ideological focus on starchy carbohydrates (bread, pasta, rice…) and a dogmatic “all salt is bad” viewpoint.

With type-2 diabetes affecting more people than ever, it is baffling why the authorities continue to emphasise carbohydrates that contribute to the development of insulin resistance.

The obvious answer to this public health crisis is to limit the intake of carbohydrates as well as sugar. We already know that type-2 diabetes can be controlled by limiting these elements. A cynical view would be that the current guidelines seem to be in hock to pharmaceutical companies whose diabetes-controlling drugs are, in fact, much less effective than dietary/lifestyle interventions in treating the condition.

Some feel that the Eatwell Guide, far from being one we should seek to emulate, encourages the consumption of nutritionally poor foods rather than nutritious alternatives. This is the view of Dr. Zoe Harcombe, PhD, who has written a stirring criticism of the guide.

Dr. Harcombe points out that 71% of the Eatwell calories come from “starch and junk”, with just 11-12% coming from beans, pulses, meat, fish and eggs. You can practically hear the author bash the keys as she types out “Carbs cannot be used for the vast majority of our daily calorie requirement.”

Even following the Eatwell Guide to the letter, then, is likely to lead to nutritional deficiencies, not to mention weight gain.

Leave a comment