The wholly unnecessary overuse of antibiotics is not just wiping out our healthy resident gut bacteria, but it’s leading to an ‘antibiotic apocalypse’.

This is the view of an increasing number of doctors, both traditional and functional/naturopathic, as well as health officers and scientists attending a recent meeting of the American Society for Microbiology (ASM).

‘A Dangerous Global Crisis’

The very real threat of antibiotic resistance is not a new one: the consequences of overprescribing drugs have been discussed in various magazines and journals since the turn of the decade. But it appears as though concerns are reaching new heights.

Public Health England is the latest body to point out the dangers of prescribing antibiotics for conditions which could just as easily be treated with rest and adequate hydration. PHE’s medical director, Professor Paul Cosford, has gone so far as to say antibiotic resistance is ‘one of the most dangerous global crises facing the modern world today.’

A new report published in the Medical Journal of Australia warns that overprescription of antibiotics could mean deaths from currently treatable conditions overtake all cancer deaths by 2050.

This is because treatments relying on antibiotics will become too dangerous to perform given the forecasted levels of resistance. Everything from conventional cancer treatments to joint replacements and abdominal surgery will be affected by the so-called drug-resistant ‘superbugs’.

At present, antibiotic resistance is spreading like wildfire across the globe. The aforementioned meeting of the ASM focused on the gene mcr-1, which provokes resistance to the powerful antibiotic colistin. Researchers learned that in one area of China, one in four hospital patients now carried the gene.

700,000 people die worldwide each year from drug-resistant infections, 5,000 of them in England. 40% of bloodstream E. coli infections can no longer be treated with first-choice antibiotics. Plot this data out on a map and the line is moving in one direction.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, at least 30% of prescriptions in the United States are unnecessary. That’s 47 million surplus prescriptions contributing to the spread of resistance and putting patients at increased risk of allergic reactions or even the C. difficile infection.

Antibiotics are akin to a forest fire raging through the microbiome, leaving behind the kind of scorched microbial landscape on which C. difficile can proliferate. For their part, Public Health England say up to 20% of UK prescriptions are ‘unnecessary’.

Antifungal Drug Resistance

It is not just antibiotic resistance which we should be worried about; growing resistance to antifungal drugs is also a cause for concern and could lead to more disease outbreaks.

Fungal infections have some of the highest mortality rates of infectious diseases, and there’s been a major increase in resistance to antifungal drugs globally in recent decades.

It’s likely a consequence of farmers spraying their affected crops with identical drugs to those used to remedy fungal infections in humans.

In lieu of effective intervention, fungal conditions afflicting humans, animals and plants will become more difficult to treat in the years ahead; particularly as more opportunistic fungal pathogens emerge.

When Are Antibiotics Unnecessary?

While antibiotics are clearly vital in certain cases – pneumonia, sepsis, bacterial meningitis – they are all too often doled out for viral infections.

It is, sadly, a two-way street: many doctors are happy to scribble a prescription for amoxicillin or cephalexin, but similarly, a large number of patients demand to be prescribed them, so convinced are they that drugs are the solution – whether to their own health challenges or their children’s.

To a degree, this behaviour is understandable: there simply has not been enough education about the dangers of antibiotic resistance. Indeed, many consider an antibiotic a panacea to every infection they could possibly be battling.

Some busy practitioners may also view the writing of a prescription as the best course of action, factoring in the time-intensive alternative of educating patients as to the long-term impact.

But as PHE rightly points out, antibiotics are simply not essential for every illness. And they should never be the first port of call for those afflicted by coughs or colds, minor infections which will naturally pass thanks to our own inherent immunity. Studies show that in such cases, antibiotics only reduce recovery time by one or two days.

Is returning to health (and the workplace) one day sooner really worth the risk of encouraging antibiotic resistance? Of course not.

How can we prevent the increasingly gloomy forecasts from coming to reality? For a start, we can stop requesting antibiotics for conditions better treated by rest, water, natural remedies and supplements.

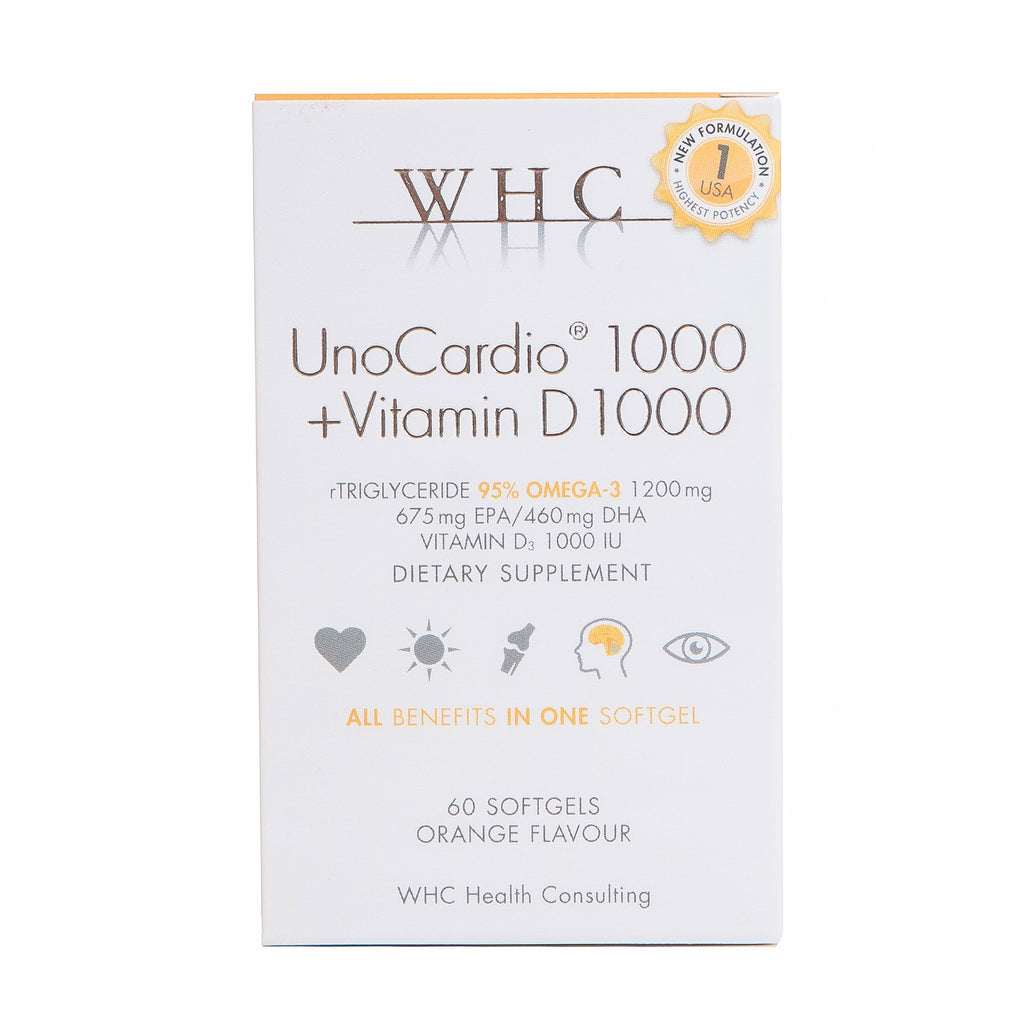

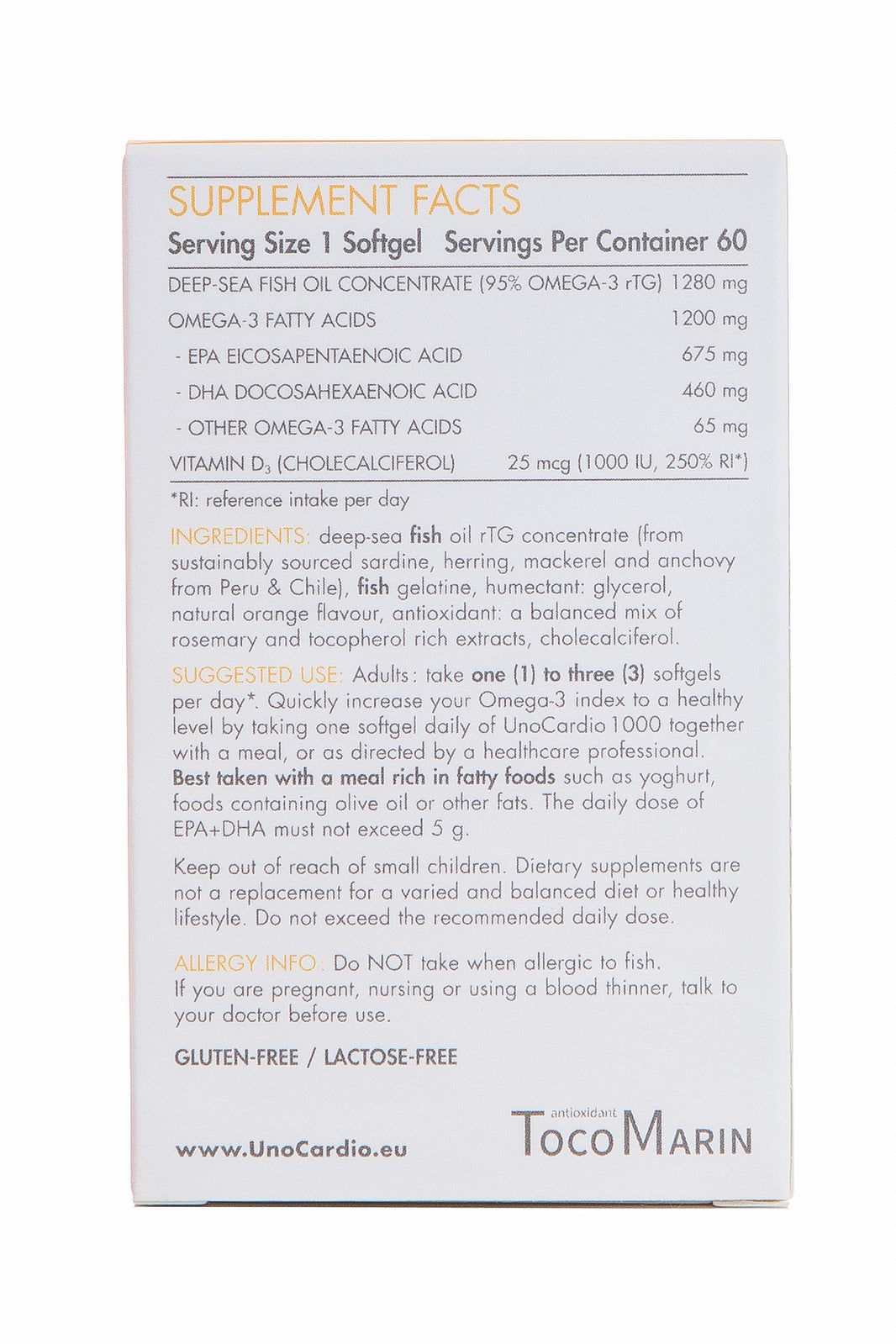

Got a sore throat, irksome earache or general flu? Put your feet up, drink plenty of water and hot drinks, and don’t skimp on your vitamins and minerals. You could avoid falling ill in the first place by keeping your Vitamin D topped up.

Overprescribing needs to be aggressively tackled in the form of physician education, too. While it’s easy to sympathise with the hectic schedules of our put-upon GPs, writing a patient a prescription to swiftly get them out of the door is just not on.

Education may take the form of rapid diagnostic tests, outlined in the ASM report and debated in Berlin a few weeks ago. These would ascertain whether an antibiotic was really necessary, rather than entrusting the treatment to an immediate assessment of patients’ symptoms.

Other methods have also been shown to work: last year, trials showed that sending monthly emails to physicians, informing them whether they were top performers in antibiotic prescribing, led to a reduction of 16%.

Other Factors Causing Antibiotic Resistance

The problem does not start and end with prescriptions. Antibiotics are routinely used in agriculture as growth promoters, fed to meat and dairy animals which then make their way on to our plates.

They’re also rife in fish farming, and antibiotics have even leached into streams and rivers as a consequent of improper disposal of industrial waste by haphazard pharmaceutical firms. The end result is drug-sodden soil, antibiotic-rich water and yet more avenues along which resistance can spread.

Needless to say, antibiotic resistance is on the rise among animals as well as humans, meaning ostensibly helpful antibiotic interventions – for controlling respiratory disease in chickens, for example – are not as effective.

It’s not just antibiotics driving antibiotic resistance; non-antibiotic pharmaceutical drugs may also be driving the problem, according to research out of Germany in 2018.

According to one molecular biologist, the post-antibiotic era is ripe for the development of new classes of germ-killing drugs. Margaret Riley of the University of Massachusetts is currently working on bacteriocin treatments, which are more discriminate than conventional antibiotics, attacking harmful bacteria without disrupting other germs in the body.

Because they are targeted and work in low doses, Riley believes the prospect of harmful bacteria engineering defences against them is unlikely.

In the meantime, we should hope that PHE’s call to action resonates loudly among patients, doctors and pharmaceutical industries. Otherwise, the cheerless prophesy about an ‘antibiotic apocalypse’ is sure to be fulfilled.

Antibiotics and Kidney Stones

New research published in 2018 shows that oral antibiotics are associated with a significantly higher risk of developing kidney stones. Perhaps the rising use of antibiotics is a factor in the growing prevalence of kidney stones in recent decades.

The study, published in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, looked at data from 13 million Brits seeking care between 1994 and 2015. It then compared 26,000 patients diagnosed with kidney stones to a control group of almost 260,000 people without kidney stones.

Researchers exposed a correlation between antibiotic use (taken 3-12 months before diagnosis) and kidney stones. Sulfas – used to remedy urinary tract infections – were linked with a 2.3 fold increase, compared to those who had not used the drugs.

Risk was elevated for up to five years, and young people were shown to be most at risk.

Focus on Good Bacteria

Those who are in the middle of an antibiotic course – or have just completed one – should prioritise replenishing the ‘good’ bacteria wiped out by the powerful drugs.

The best way of doing so is to nourish the gut with human-derived probiotics such as those created by the International Probiotics Institute.

Progurt contains one trillion Colony-Forming Units per sachet, far more than any other probiotic currently available. What’s more, its species-specific strains are intuitive to the human gastrointestinal tract, making them better able to colonise and have a long-term impact.

Because one sachet of Progurt contains more beneficial bacteria than a month’s supply of many probiotic products – 1 trillion CFU versus 10 or 20 billion – you generally don’t have to take Progurt on a daily basis. A sachet every other day, or even once a week, could work wonders for your microbiome.

Leave a comment